[Note: this article is being published in 2021 but was written in 2019. Some sections caused a several year delay, but I’ve concluded that I won’t finish them anytime soon and so have just removed them. They may constitute the contents of a future article.]

The last decade has seen a radical increase in the cultural visibility of transgenderism. At the same time, the rate at which people identify as transgender or non-gender conforming has risen to something like 2% of adolescents (Struass, 2019).

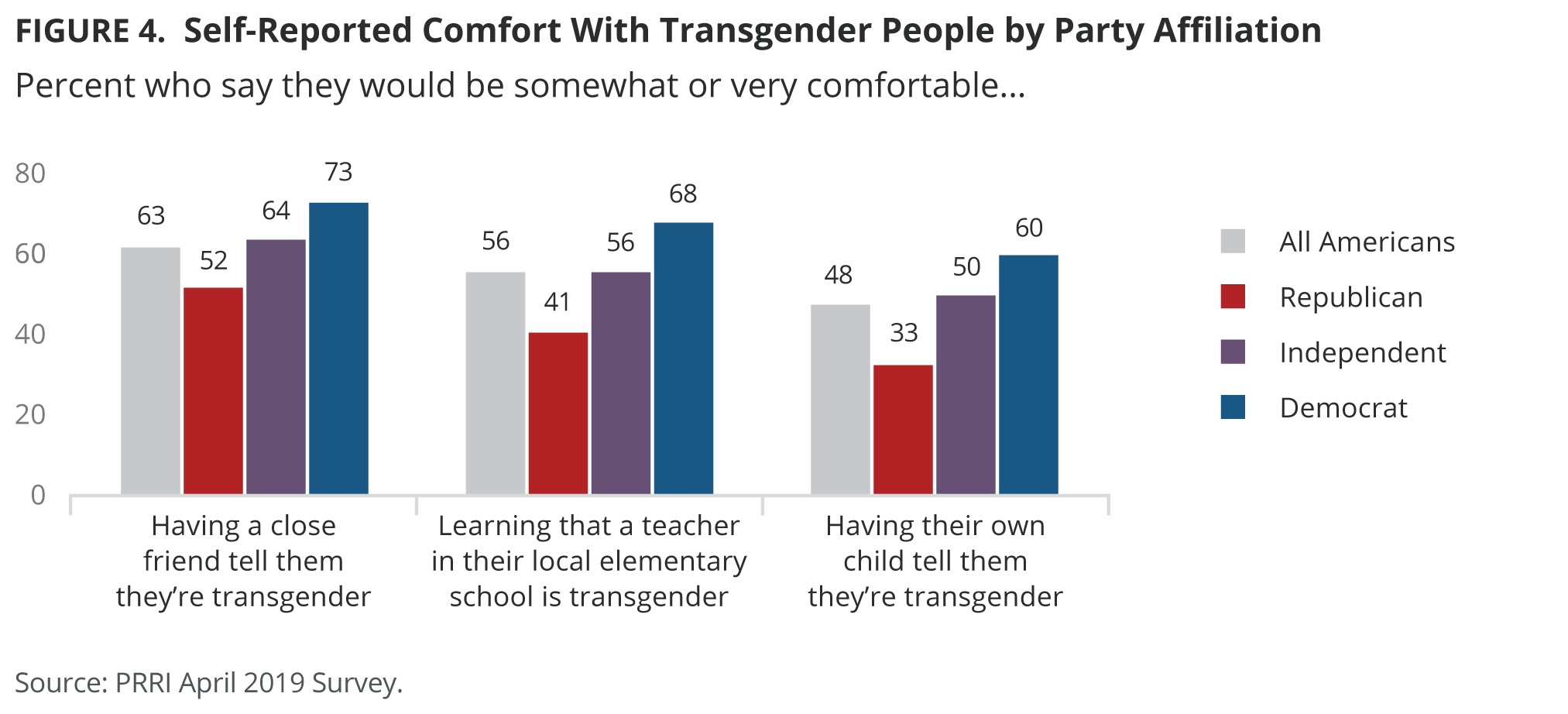

For the most part, Americans have responded to this shift by adopting more liberal attitudes towards trans-gendered individuals. Today, most Americans say they would be comfortable having a transgender friend or learning that a local teacher is transgender. Americans also favor letting trans people into the military and nearly half of the population says they would be comfortable with having a transgender child.

The public is pretty divided concerning bathrooms with a slim majority saying that people should use bathrooms according to their biological sex rather than their gender identity.

Among adults under the age of 35, the vast majority say they would be comfortable having a gay or trans child, though there has been a moderate increase in the last year or so in those expressing discomfort with this.

The public hasn’t shifted such that the super majority of people take a perfectly left wing view on transgenderism, but the state of public opinion is obviously a great deal more left leaning than it was ten years ago when trans-acceptance wasn’t even a mainstream political issue.

The last decade has also seen the popularization of certain theories, explanations, and narratives surrounding transgenderism. While not monolithic, many on the left have often said something like the following:

Transgenderism occurs when people want to be a gender that is discordant with their prescribed sex. This is caused by a mismatch between people’s neurological and psychological sex on the one hand, and their genetic sex on the other. Many people are not accepting of trans-people, and their discriminatory behaviors and ideas cause trans people to exhibit a multitude of behavioral and psychological problems. These problems should be solved by lessening anti-trans discrimination, and maximizing the ease with which trans people can transition into their preferred gender. Cis people have no good reason to resist changing norms in this way, because accepting the validity of trans-genderism implies no significant imposition on them and is really just a matter of letting other people live as they wish to.

The rest of this post will be aimed at showing that each part of this story is false.

Discrimination and Trans Suicide Rates

Looking at data from the 2015 US Transgender survey (n=27,715) on suicide rates, we find that among the general population only 0.6% of people have attempted suicide within the last year, but among trans people this rate is 7.3% or 12 times the rate of the general population. In this section, I am going to argue that most of this gap cannot be explained by discrimination.

A first reason to doubt that discrimination is a complete explanation for the mental health problems of trans people stems from the fact that trans people who report not having experienced discrimination still exhibit elevated suicide risk. Across seven studies, the average lifetime suicide attempt rate among such trans people was 24% or 5.2 times that of the general population (4.6%, from Herman et al).

| Citation | Discrimination Type | Rate |

| Goldblum et al. (2012) | School based GBV | 0.14 |

| Bauer et al. (2015) | Harassment / Violence | 0.18 |

| Clements-Nolle et al. (2006) | Gender Discrimination | 0.16 |

| Testa et al. (2012) | Physical Violence | 0.14 |

| Testa et al. (2012) | Sexual Violence | 0.19 |

| Seelman (2016) | Victimized by Students | 0.43 |

| Seelman (2016) | Victimized by Teachers | 0.45 |

Similarly, in Herman et al. (2019) the past year suicide attempt rate among trans people reporting having been the victim of zero cases of significant discrimination within the last year was 5.1% or 8.5 times the rate of the general population.

Importantly, most acts which constitute discrimination, ostracizing someone, insulting someone, emotionally or physically hurting someone, etc., are essentially forms of bullying. This fact matters because even though there is a substantial correlation between bullying and suicide rates the causal relationship between bullying and suicide is much weaker than this correlation suggests. To be specific, a one standard deviation increase in bullying predicts a 68% increase in the odds of someone attempting suicide. However, if you use a twin study design to control for genes and the family environment, and also control for psychopathology that pre-existed the bullying, we find that a one standard deviation increase in bullying only predicts a 25% increase in the odds of attempting suicide (Oreilly et al., 2021). Thus, only roughly a third (37%) of the commonly noted association between bullying and suicide is plausibly causal.

Given this, it is likely that trans people who experience no discrimination are advantaged above the average trans person in terms of their pre-existing psychopathologies or genetic predisposition towards suicide or both. So the above figures represent suicide rates which, though much higher than average, are lower than what we would rationally expect if the average trans person experienced no discrimination.

A second reason to doubt a mostly-discrimination explanation for trans suicide rates is that suicidal LGBT people usually don’t cite discrimination as a cause of their behavior. In fact, a 2021 meta-analysis found that the vast majority (74%) of LGBT youth (age: 12 – 25) who have attempted suicide answer “no” when asked if they’ve personally been the victim of various sorts of anti-LGBT discrimination and bullying (Williams et al., 2021). Of course, a short coming of this line of research is that it includes non-trans LGBT respondents, but it is still relevant enough to be worth mentioning.

A third line of evidence against the discrimination hypothesis consists in the fact that the relationship between discrimination and suicide among trans people is statistically quite weak. If discrimination did play a big role in trans suicide rates, we might expect for trans people who have experienced a great deal of discrimination to report suicide attempt rates far higher than those who have not. But when reviewing all the literature I could find in 2019 on the association between suicide and non-violent discrimination among trans people (22 effects), I found, in the first place, that the effect sizes reported were generally small, especially in larger studies. Among studies with at least 1,000 participants, experiencing non-violent discrimination predicted a roughly 10% increase in suicidal behavior. Moreover, a majority of these effects (64%) were not statistically significant, so most of the research did not find that non-violent discrimination significantly elevated suicide risk among trans people.

| Citation | Predictor | Outcome | Effect Size | N |

| Goldblum et al. (2012) | School Based Gender Victimization | Attempt | OR = 3.8 | 290 |

| Marshall et al. (2016) | Internalized Stigma | Attempt | OR = 2.06 | 482 |

| Marshall et al. (2016) | Discrimination in Healthcare | Attempt | OR = 1.25 (NS) | 482 |

| Perez-Brumer et al. (2015) | Structural Stigma | Attempt | OR = 1.01 (NS) | 1060 |

| Perez-Brumer et al. (2015) | Structural Stigma | Attempt | OR = .96 | 1060 |

| Perez-Brumer et al. (2015) | Internalized Transphobia | Attempt | OR = 1.18 | 1060 |

| Lehavot et al. (2016) | Housing Discrimination | Attempt | OR = 1.02 (NS) | 212 |

| Lehavot et al. (2016) | Employment Discrimination | Attempt | OR = 2.13 (NS) | 212 |

| Lehavot et al. (2016) | Heterosexism | Attempt | OR = .78 (NS) | 212 |

| Lehavot et al. (2016) | Military Stigma | Attempt | OR = .67 (NS) | 212 |

| Clements-Nolle et al. (2006) | Verbal Discrimination | Attempt | OR = .84 (NS) | 491 |

| Kuper et al. (2018) | Gender Discrimination | Attempt | OR = 1.08 | 1896 |

| Trujillo et al. (2017) | Harassment/rejection Discrimination | Attempt | b = .17 (NS) | 78 |

| Maguen et al. (2010) | Verbal Threat | Attempt | b = .04 (NS) | 141 |

| Rood et al (2015) | Gender Discrimination (1 type) | Ideation | OR = 2.09 | 350 |

| Rood et al (2015) | Gender Discrimination (2 types) | Ideation | OR = 2.86 | 350 |

| Rood et al (2015) | Gender Discrimination (3+ types) | Ideation | OR = 1.83 (NS) | 350 |

| Lehavot et al. (2016) | Housing Discrimination | Ideation | OR = 3.88 (NS) | 212 |

| Lehavot et al. (2016) | Employment Discrimination | Ideation | OR = .76 (NS) | 212 |

| Lehavot et al. (2016) | Heterosexism | Ideation | OR = .91 (NS) | 212 |

| Lehavot et al. (2016) | Military Stigma | Ideation | OR = .80 (NS) | 212 |

| Kuper et al. (2018) | Gender Discrimination | Ideation | OR = 1.12 | 1896 |

I found something similar when looking at 22 reported associations between a lack of social support and suicide, with the effect sizes being very weak, meaning that can’t possibly explain more than a tiny fraction of the association between transgenderism and suicide, and once against the effects were statistically insignificant most (78%) of the time.

| Citation | Predictor | Outcome | Effect Size |

| Yadegarfard et al. (2014) | Family Rejection | Suicide Risk | NS |

| Yadegarfard et al. (2014) | Social Support | Suicide Risk | NS |

| Tebbe et al. (2016) | Friend Support | Suicide Risk | b = -.14 |

| Tebbe et al. (2016) | Family Support | Suicide Risk | b = -.04 (NS) |

| Bauer et al. (2015) | Parental Support | Ideation | 0.43 |

| Bauer et al. (2015) | Family Support | Ideation | 0.66 (NS) |

| Bauer et al. (2015) | Leader Support | Ideation | 1.02 (NS) |

| Bauer et al. (2015) | Peer Support | Ideation | 0.67 (NS) |

| Zhu et al. (2019) | Family Support | Ideation | 0.99 (NS) |

| Zhu et al. (2019) | Friend Support | Ideation | 0.97 (NS) |

| Zeluf et al. (2018) | Social Support | Ideation | 1.47 |

| Zhu et al. (2019) | Family Conflict | Attempt | 1.59 |

| Zhu et al. (2019) | Family Support | Attempt | 0.96 |

| Zhu et al. (2019) | Friend Support | Attempt | 0.99 (NS) |

| Trujillo et al. (2017) | Family Support | Attempt | b = -.03 (NS) |

| Trujillo et al. (2017) | Friend Support | Attempt | b = -.04 (NS) |

| Trujillo et al. (2017) | SO Support | Attempt | b = -.08 (NS) |

| Lytle et al. (2017) | Family Support | Attempt | 0.96 (NS) |

| Lytle et al. (2017) | Friend Support | Attempt | 1.02 (NS) |

| Klein et al. (2016) | Moderate Family Rejection | Attempt | 1.96 |

| Klein et al. (2016) | High Family Rejection | Attempt | 3.34 |

| Zeluf et al. (2018) | Social Support | Attempt | 1.17 (NS) |

The data concerning physical violence is less clear. Across ten effects, the link between physical violence and suicide was more consistently statistically significant. However, the size of the effect reported varied a great deal between studies. The degree to which experiencing violent discrimination elevated suicide risk ranged from 1.43 to 4.72. Moreover, there was an tendency for larger studies to find smaller effects. The largest study I found reported odds ratios of less than 2.

| Citation | Predictor | Outcome | Effect Size | N |

| Rood et al (2015) | Physical or sexual violence | Ideation | OR = 4.18 | 350 |

| Rood et al (2015) | Physical and sexual violence | Ideation | OR = 5.44 | 350 |

| Marshall et al. (2016) | Police Violence | Attempt | OR = 1.43 (NS) | 482 |

| Clements-Nolle et al. (2006) | Physical Discrimination | Attempt | OR = 1.77 | 491 |

| Testa et al. (2012) | Physical Violence (M) | Attempt | OR = 4.36 | 92 |

| Testa et al. (2012) | Physical Violence (F) | Attempt | OR = 5.3 | 179 |

| Testa et al. (2012) | Sexual Violence (M) | Attempt | OR = 4.72 | 92 |

| Testa et al. (2012) | Sexual Violent (F) | Attempt | OR = 4.21 | 179 |

| Maguen et al. (2010) | Transgender Violence | Attempt | b = .24 | 141 |

Consistent with my review, a 2022 meta-analysis found that experiences of discrimination correlate at only 0.24 with a trans person’s risk of suicide attempt. Expectations of rejection was an even weaker correlate at 0.15 and internalized transphobias exhibited a still weaker and marginally significant correlation of 0.09 (Pelicane et al., 2022). These effect sizes entail that no measure of discrimination explains even 5% of the variance in the rate at which different trans people attempt suicide.

Given the extremely weak effects of other sorts of discrimination on suicide, it is clear that the combination of physical discrimination, non-physical discrimination, and lack of social support, cannot account for anywhere near half of the trans-cis suicide gap. And this is prior to adjusting our estimates for the fact that, as mentioned previously, most of the association between discrimination and suicide is likely non-causal.

Finally, international data seems to imply that discrimination has very little at all to do with trans suicide rates. I say this because there is no obvious association between the suicide rate of trans people and the trans-acceptance of the place they live in. Sweden has a lower rate of trans suicide than the US, but the US has a lower rate than Canada, and no region I found data on has as low of a rate as china. Thus, lower national rates of trans-acceptance don’t seem to lead to lower levels of trans suicide, a finding hard to square with the notion that the link between discrimination and suicide is causal.

| Citation | Location | Rate |

| Clements-Nolle et al. (2006) | San Francisco | 0.32 |

| Zeluf et al. (2018) | Sweden | 0.32 |

| Kaplan et al. (2016) | Lebanon | 0.46 |

| Zhu et al. (2019) | China | 0.16 |

| Marshall et al. (2016) | Argentina | 0.33 |

| James et al. (2015) | USA | 0.4 |

| Scalon et al. (2010) | Ontario | 0.43 |

Obviously, we can’t run randomized experiments to see how much discrimination influences suicide. Instead, we have to rely on observational data. That data, such as it is, makes it fairly implausible that discrimination explains the majority of the trans-suicide gap. Moreover, the data is surprisingly consistent with the notion that discrimination plays only a very small role in trans suicide rates. Perhaps most importantly, the data makes very clear that it would be irrational to expect the trans suicide rate to mirror anything like that of the general population’s in a world with no anti-trans discrimination.

Gender Expression and Trans Suicidality

Of course, the other major tenant of the mainstream narrative on transgenderism is that trans people’s mental health is also brought down by the fact that they often cannot engage in a mode of gender expression which is consistent with their internal gender identity. In this section I’ll argue that it is unclear whether aligning trans people’s gender identity and gender expression improves their mental wellbeing and that it is clear that doing so does not improve trans mental health nearly enough to bring them inline with the general population.

The first thing to say is that there are some studies which find that transitioned trans people have lower levels of suicidality than do non-transitioned trans people. For instance, in a sample of 314 transwomen from San Francisco, Wilson et al. (2014) found lifetime suicidal ideation rates of 75% for trans people who hadn’t received any medical intervention, 74% for those who had genital surgery, and 51% / 52% for those who had taken hormones or had breast surgery. However, though this provides some support for transition it is also important to note that around the time at which these trans people were interviewed, the lifetime suicidal ideation rate for the US population was 15.6% (Nock et al., 2008). Thus, even when trans people both had transitioned and were living in possibly the most pro-LGBT city on earth, their rate of suicidal ideation was still 3.3 times that of the general population.

Other research has found transitioning and open gender expression to be unrelated to trans suicidality though such studies have often suffered from small sample sizes and low statistical power (e.g. Bauer et al., 2015; Zeluf et al., 2018; Lehavot et al., 2016; Amand et al, 2011).

That said, the highest quality research has found that trans people’s transitioning is associated with elevated rates of suicidality. For instance, in Haas et al. (2014)‘s analysis of data on 5,885 trans Americans it was shown that life time suicide attempt rates were higher among trans people who have transitioned, or who want to someday, compared to trans people who had no plans to actually transition despite the tension between their assigned and internally felt gender identity.

Relatedly, in a sample of 1,309 trans Chinese, Chen et al (2019) found that trans people seeking sex reassignment surgery had a rate of suicidal ideation 76% greater than did trans people not seeking such a surgery. And in Rood et al. (2015), planning to transition and having already transitioned were both associated with a nearly 3x increase in the odds of lifetime suicidal thoughts (n=350).

The repeated finding that even wanting a transition related surgery is a risk factor for suicide is important to note as it implies that the high suicidality among post-operation trans people is caused by something which pre-dates the operation itself.

Most significantly, Herman et al. (2019) looked at data on 27,715 trans Americans and found a past year rate of suicide attempt of 4.1% among trans people who say they don’t want to actually live in their gender identity someday compared to 5.2% among those who were unsure and 7.4% among those who did. The study also recorded a past year suicide attempt rate of 5.1% among trans people who had already had a transition related surgery and 8.5% among trans people who wanted such a surgery but who had not yet been able to have one.

This research brings forth two questions: First, why do trans people who are currently living in alignment with their own gender identity, and trans people who plan to at a later date, have elevated suicide rates compared to trans people who decide they don’t want to do this? Second, why do trans people who want to get a transition related surgery but can’t have the most elevated suicide rates of any group I’ve mentioned?

One possible explanation is that those trans people who want to actually transition have greater levels of gender dysphoria than do trans people who do not making comparisons between their suicide rates misleading. We might add that the high suicide rate of trans people who want to transition but cannot makes a fairer comparison because these are people who have as much gender dysphoria as do those who have transitioned.

There are two major problems with this line of reasoning. First, the placebo effect, and the distress someone would likely feel if they thought there was medicine which could help them but which they could not access, and the fact that whatever is stopping someone from getting a surgery they want is probably itself negatively related to well being, make trans people who want but cannot get transition related surgeries obviously invalid as a comparison group. Second, the fact that suicide rates don’t significantly differ between trans people who have had such surgeries and who are merely planning to is hard to explain on this sort of hypothesis.

Actually, there are two reason’s we’d expect post surgery suicide rates to be lower than pre surgery ones even if the surgery had no effect. First, there is the placebo effect which is virtually universal across medical research. Second, transitioned people are presumably older than trans people who merely plan to transition in the future and in general older trans people have lower suicide rates than do younger ones (Herman et al., 2019). Given this, the equality of the rates of suicide across these groups is more plausibly interpreted as the surgery having a modest detrimental impact on suicide risk than it is interpreted as having a protective one.

My preferred explanation for this pattern of findings is this: in general it is unhealthy to attempt the change things which you cannot change and which are outside of your control. Moreover, it is unhealthy to allow your happiness to be contingent on things like what clothes you wear, how you speak, the details of how others speak to you (pronouns), your body image beyond the concern of physical health, and the other concrete things which define gender roles. This is what a man is doing when they place great significance on attempting to be a woman or vice versa. It is possible, and optimal, to recognize the desire to be a different gender without letting this desire control you and have you attempt the impossible. The more you lean into this desire, the more the impossibility of its satisfaction will harm you, though perhaps no condition will harm you as much as thinking that the desire could be satisfied if only you could have an operation which is available to others but not yourself.

Of course this is just speculation, but it is consistent with the full pattern of data and a more general view of how people should relate to their desires. Regardless, it is now hopefully clear that the data does not justify the view that transitioning lowers suicide rates and refutes the view that transitioning leads trans people to have a level of wellbeing comparable to cisgendered people.

Proponents of the standard treatment for transgenderism may respond by noting that people say they feel better after undergoing medical transitions (Murad et al. 2010; Millet et al., 2017). Throughout this post so far, I’ve followed a methodological choice to use suicide as the outcome of interest rather than self reported scores on scales for outcomes like depression and anxiety. This is because people don’t like to admit it when they make mistakes. Everyone is naturally biased in favor of decisions that they have already made. Thus, looking at subjective ratings by people who have undergone various procedures is not very informative. Data on suicide rates are preferable because suicidality is a more concrete and objective criterion.

I’ve argued that the data on suicide suggests that transitioning does not help trans people, but the data from self-reported emotion and satisfaction suggests the opposite. I feel the best explanation for this divergence of results is exactly the sort of bias that caused me to only look at suicide data in the first place. Someone offering an alternative to this analysis will need to come up with a better explanation than this for why the outcomes diverge, as well as an explanation for how it can be that these treatments improve trans people’s mental health but not their suicide rates.

In combination, the last two sections imply that the left’s explanation for trans suicide rates, discrimination and a lack of free gender expression, clearly fails to account for the vast majority of why it is that trans people have such high suicide rates.

The Mismatched Biology Hypothesis

Let’s next examine the notion that trans people, due to genes and the prenatal environment, have brains which match the typical member of the gender they identify with.

Guillamon et al. (2016) provides a useful review of the research on transgenderism as of 2016. Research then indicated that while trans people were similar to the opposite sex in a few brain regions most of their brains more closely resembled the typical member of their own sex.

The same result was found in Frigerio et al. (2021)‘s review of brain imaging work done up to 2018.

Importantly, both reviews note that this research is massively confounded by the prevalence of homosexuality among trans people. So, it could be, for example, that MtF people have somewhat feminized brains simply because they tend to be gay, while their transgenderism may be causally unrelated to these neurological trends.

I’m aware of only two studies which have directly accounted for this. First, Savic et al. (2011) from the brains of heterosexual male-to-female trans people were not abnormally feminized. Second, Burke et al. (2017) found that after controlling for sexual orientation trans people’s brains were mostly typical of their sex. The one exception to this was the right inferior fronto-occipital tract. However, even here the brains of transgender people were not typical of those of any sex. That said, all this research is based on small samples and so not much can be said with confidence about the neurological correlates of transgenderism.

The brain story is also complicated by the fact that sex differences in the brain, while real, are not that large. For most brain differences, there is a good deal of overlap between men and women, so that there are presumably lots of people with sex atypical brains and the vast majority of them are not trans.

Moving on to hormones, the ratio of the length of people’s 2nd and 4th finger is a correlate of pre-natal testosterone, and so trans people having digit ratios typical of the other sex would be evidence for them having an atypical pre-natal environment for their sex.

Voracek et al. (2018) meta-analyzed the research on this topic and found the following:

“MtF cases have feminized right-hand (R2D:4D) digit ratio, g= 0.190 (based on 9 samples, totaling 690 cases and 699 controls; P= .001, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.076 to 0.304), whereas the directionally identical effect for left-hand (L2D:4D) digit ratio was not significant, g= 0.132 (6 samples, 308 cases, 544 controls; P= .07, CI: –0.012 to 0.277). FtM cases have neither masculinized R2D:4D, g= –0.088 (9 samples, 449 cases, 648 controls; P= .22, CI: –0.227 to 0.051) nor masculinized L2D:4D, g= –0.059 (6 samples, 203 cases, 505 controls; P= .51, CI: –0.235 to 0.117).”

So, this story doesn’t work for FtM trans people and only works for MtF trans people when we are talking about the right hand. Moreover, the effect size here is 0.19. This is a quite small effect size. Assuming digit ratios are normally distributed, this would imply that the average MtF trans person has a digit ratio more masculine than 42% of males. This variable may have some role in a full explanation of transgenderism, but the vast majority of males with hands that feminized are not trans, and so this is at best a weak explanatory factor.

Twin studies should be informative both with respect to genes and the prenatal environment, but researchers have only been able to find a handful of twin pairs in which at least one twin is transgender. Heylens et al. (2012) aggregated data from previous studies and found a concordance rate for transgenderism of 0% among 21 non-identical twin pairs and 39% among identical twin pairs. A later study from Japan produced similar results in terms of low concordance rates among twins for Gender Identity Disorder (Sasaki et al., 2016). The fact that concordance rates are higher among identical twins than among non-identical twins implies that genetics does play a role in transgenderism, as it does in all human behavior, but the fact that concordance rates even among MZ twins are well below half suggests that genetics and the pre-natal environment are far from a sufficient explanation of transgenderism. Moreover, to the degree that pre-natal environments and genetics do play a role, that role does not primarily seem to be one of creating people whose biology matches the other sex, as evidenced by neurological data and data on digit ratios.

Aside from being empirically unsupported, the idea that transgenderism is caused by trans people having brains typical of their preferred sexual identity implies some very strange things about the relationship between brains and sexual identity.

If my brain were to become feminized, I would probably acquire a more female-typical personality, for instance I might become more agreeable and less emotionally stable, and perhaps I would develop different pre-dispositions about who to have sex with, how many people to have sex with, and the role I’d want to play in raising children. This all seems plausible.

However, there is no obvious connection between having a female typical brain and wanting to wear female typical clothing, or wanting to posses a female body, or wanting to be called a woman, etc. Plausibly, people identify with their own body because the brain is wired to identify with whatever body it finds itself in. This would explain why I feel a sense of identity not only with my sex, but also specifically with the body that is mine. It would be very non-parsimonious, and entirely speculative, to suggest that brains are built to identify with certain sorts of bodies and that if a part of my brain where changed in shape or size to be more typical of a woman then I would desire to have a female body.

It is equally speculative to suggest that women would want to wear feminine clothing even if they didn’t have the feminine bodies that such clothing is made for.

Of course, it would be entirely unreasonable to suggest that women want to be referred to using feminine pronouns because they have female typical brains. Generally speaking, women want to be called women because they are women, in the most essentialist since of the term, and this is true even of women who are psychologically abnormal for their sex.

Thus, the very notion that a mismatched brain causes transgenderism implies speculative seeming assumptions about the nature of gender identity in general. Of course, sometimes surprising things turn out to be true, but we should only accept such claims as true in response to rigorous evidence and never in response to political bullying.

Transgenderism, Tolerance, and the Meaning of Gender

Finally, let’s consider the idea that acceptance of trans genderism amounts to little more than letting other people live and identify as they wish to. Framed this way, acceptance of transgenderism seems like little more than an act of basic tolerance.

I regard this framing as misleading because transgenderism is often as much about how trans people want other people to treat them as it is about anything internal to themselves. Specifically, trans people often want others to treat them as if they are typical members of their preferred sex.

Consider their insistence that people use their “preferred pronouns”. If I call a trans-man a woman, the two of us both know that I mean they have no Y chromosome, and we both agree on this fact. We both also obviously know that the person in question calls themselves a man. So what is the disagreement that causes trans people to be upset in such instances? Presumably, it is because using a non-preferred pronoun amounts to a more general refusal to treat trans people as if they are a typical member of the sex they identify with.

Pronoun use, on its own, isn’t that big of a deal. It is therefore unfortunate that so much time as been spent focusing on pro-noun use, one of the most shallow aspects of what it means to be treated like a man or a woman. This focus has led to the impression that trans people may be asking something of cis people, but that it doesn’t amount to much more than a simple change in language.

But treating someone like a typical member of their self identified sex is about more than mere words.

This is most obvious with respect to sex. For a heterosexual male to treat a trans woman as if they were a normal female would mean that they would consider them to be people they’d potentially like to have sex with. While I’ve not seen a survey on the matter, I feel fairly confident that most heterosexual men feel as I do and find the notion of having sex with a trans-female to be rather unpleasant. This would be true even if the trans-female looked indistinguishable from a cis-female.

Something similar occurs with respect to instincts surrounding protection. Males instinctively feel protective of females in a way that we do not for fellow males. For instance, if a female is physically assaulted by a male most males feel that they should intervene and this does not occur when males are seen fighting each other even if there is a significant physical disparity between the males in question. Relatedly, we place a higher value on sustaining the innocence of young girls than we do young boys. The idea of treating a biological male as a female in these ways seems obviously absurd.

This takes us naturally into the debate surrounding trans people in sports. Trans people argue that they should be able to participate in sports leagues intended for the gender they identify with. To make things fair, trans-females have proposed various medical routes by which they might eliminate the physical advantages that males naturally have over females. The efficacy of such attempts is controversial, but I don’t think it really matters because this whole argument rests on a misunderstanding of why sports are segregated to begin with.

If the argument of trans-advocates made sense, we should generally allow males into female sports so long as their ability was within the plausible range of ability for female athletes. This could occur for any number of reasons. Some males are naturally weaker and slower than average. Some males simply put very little effort into athletic ability. Or it could be because a male injected themselves with hormones or a drug that lessened their physical capabilities.

If the point of sex-segregated sports was just to stop people of unequal ability from competing then we wouldn’t even have sex segregated sports. We would have ability-segregated sports and women would just disproportionately end up in the low-ability leagues for many sports. But we dont, we have sex segregated sports and this reflects the fact that people generally think the sexes should be treated differently independent of any feature other than sex itself.

At its most fundamental level sex is about mating and reproduction. In large part, the reason for which men treat women like we do is because we see them as potential sexual partners, mothers, daughters, and grand mothers. I assume a similar thing is true of why women treat men the way they do. Truly treating trans people as a member of their preferred sex would therefore clearly involve more than a mere shift in language. It would require us to do things which naturally cause reactions of disgust and discomfort for many cis gendered people. In some cases, such as the domain of sexual attraction, treating trans people as their preferred sex would even violate many cis people’s sense of their own identity.

This gives us good reason to refuse to treat trans people as they want to be treated. Of course, you might say that this is just a mental hang up of cis people and that they should learn to get over it rather than imposing things on others. But then cis people might say the exact same thing to trans people. This may make it seem as if both groups want something which may cause the other group suffering, and so they have fundamentally divergent interests such that any compromise is impossible. By necessity, one group will win and the other will lose. Unfortunately, this seems to me like it is probably true so long as trans gender people are convinced that pursuing their desire to be a member of the opposite sex is in their interest.

Conclusion

In this article I’ve tried to show that trans-genderism is not primarily the result of “mis matched” biology, that the desires of trans people require a good deal more than mere tolerance from cis people, and that the mental suffering of trans people is not primarily the result of discrimination nor can it be cured by trans people attempting to look and act like their preferred sex. I have not tried to explain why it is that trans people want to be a member of the opposite sex, or why they experience so much mental suffering. I don’t think we have good answers to either of these questions, and in any case removing existing explanations about trans genderism is useful to do prior to offering any alternative explanation.

Great article

LikeLike

Hi Sean,

I don’t see where you have distinguished between the two types of transgendered – Homosexual Transexuals and autogynephiles. They are very different and I believe they will have different rates of suicide and other problems. I didn’t look at each study but how many of those studies make a distinction between the two?

This is a massive problem. There’s no way to talk about transgenderism without understanding and pointing out the differences.

Also have you watched and or read http://www.rodfleming.com videos and articles on transgenderism?

Good luck in your studies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good work and well presented. Really appreciate the work you do Sean.

LikeLike

Hello,

I’ve started reading your blog only recently and transgenderism was another riveting read. Thank you for sharing your work.

There is one argument I wished to point out as debatable. In the end of your essay, before conclusion you compare cis people and trans people as equal groups whose interests lie in direct conflict. (Equal here as a measure of contribution to conflict.) While I fully agree with how you describe their respective interests, I do not believe them to be equal. There is a fundamental difference as trans people are the ones who made the choice of becoming a separate group voluntarily and acted on that choice, while cis people did nothing remaining passive participants. From this follows that the conflict appears as a consequence of actions taken by trans people. From the point of fairness then, trans people should be the ones to carry full responsibility for their actions without making demands of cis people as each [adult] person is responsible for their respective choices and actions and life.

LikeLike

Good article kiddo

LikeLike

Hey, Sean. I really like your article! However, I was wondering what you thought of this meta-analysis:

https://whatweknow.inequality.cornell.edu/topics/lgbt-equality/what-does-the-scholarly-research-say-about-the-well-being-of-transgender-people/

Of 56 studies, 52 indicated transitioning has a positive effect on the mental health of transgender people and 4 indicated it had mixed or no results. Zero indicated negative results.

Was this study conducted poorly?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here are some other studies:

Click to access Mental-Health-and-Self-Worth-in-Socially-Transitioned-Transgender-Youth.pdf

– Study done in 2016 found that transgender children reported depression and self-worth that did not differ from their matched-control or sibling peers

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25201798/

– Study done in 2014 found that: “After gender reassignment, in young adulthood, the GD was alleviated and psychological functioning had steadily improved. Well-being was similar to or better than same-age young adults from the general population. Improvements in psychological functioning were positively correlated with postsurgical subjective well-being.”

http://transpulseproject.ca/research/impacts-of-strong-parental-support-for-trans-youth/

– Study in 2012 found that the suicide rate amongst transgender youth dropped drastically after parental support

https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/suicidality-transgender-adults/

– Study done in 2019 found that access to gender-affirming medical care is associated with a lower prevalence of suicidal thoughts and attempts

LikeLiked by 1 person

Most of the studies were badly designed ie: small sample sizes, no controls etc.

See: https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2019/04/51524/

LikeLike

Thats not a meta analysis, its just a literature review that includes mostly studies that have small sample sizes and they have no controls

LikeLike

Very informative article, great work Sean!

I’m gonna play devil’s advocate though and point to a few potential counterarguments that critics may bring up.

1. When discussing the suicide rates in different regions you mention that the US has a lower suicide rate than Canada. However, the study you cite in the table only looked at the suicide rate of Ontario. One might argue that there could be potential regional differences within Canada concerning transgender acceptance and that you intentionally conflated Ontario with Canada as a whole.

2. You also list the suicide rate in China. Many people would probably doubt the veracity of Chinese statistics, as they are known to manipulate data in other areas.

3. There are numerous studies showing suicide (attempt) rates to decrease after transition. Basically any article found via a quick search on Google scholar shows this to be true (which isn’t surprising considering Google’s bias). Why didn’t you address such studies?

Apart from these points, it would be interesting to see an analysis of how long potential positive effects of transitioning on mental wellbeing last. I imagine there is a period where people are still too invested in their choice to admit any wrongdoing. Furthermore, you should look at desistance rates (i.e., how many transgender people translation back to their original sex), as this might yield some interesting insights.

In any case, keep up the good work Sean! You’re by far the best researcher on the dissident right and always a go-to source for debunking leftist lunacy. And tell Ryan to stop being a lazy cunt, we miss him.

LikeLike

On the HSTS/AGP stuff another comment mentioned: Kay Browns wordpress blog may be of interest – ‘sillyolme’ (no link because im not sure this comment will go through with one)

LikeLike

Pingback: Asa Hutchinson Goes Wobbly on Trans Kid Bill - Victory Girls Blog

Pingback: Asa Hutchinson Goes Wobbly on Trans Kid Bill - United Push Back

Hi Sean, on your recent discussion with Richard Spencer you mentioned that there are studies showing trans people are more likely to be controlling, can you expand on that? I can’t find those studies, thanks!

LikeLike

I’ve tweeted about some of the relevant research here:

LikeLike

Hey Sean! Went through some of the data in your Treating Gender Dysphoria section and it appears that you have misrepresented a ton of the studies you site in a number of ways. I am assuming these are just mistakes and not intentional misuse of stats. I will write a blog post on it and DM it to you soon.

LikeLike

Also, given how misleading that section is, I am assuming you made similar mistakes in the other sections, so I will go through those as well just in case and include my issues in the post

LikeLike

Link to the post?

LikeLike

Post the article please!

LikeLike

Have you seen the analyses in the comments? Could you provide a rebuttal to them?

LikeLike