In this post, I am going to critique the literature linking ethnic diversity to low levels of social cohesion.

The Putnam Study

Putnam (2007) is easily the most often cited paper to show that diversity negatively impacts communities. Putnam shows that participants from more diverse regions reported lower levels of social capital, the degree to which neighbors interact with and trust one another, even after controlling for individual and regional differences in social and economic variables.

Before controlling for confounding variables, the relationship between an area’s level of trust and ethnic diversity looked strong and negative.

What is often ignored in second-hand accounts of this paper is that the multivariate effect, the impact of diversity after controlling for all these confounding variables, was statistically significant but minuscule. Local ethnic diversity independently accounted for less than 1% of the variation in trust.

Moreover, it wasn’t the strongest effect measured. At the individual level, the best predictors were, in order, a participant’s age, whether they owned a home, their level of education, and whether they were Black. The strongest regional predictors, in order, were census tract poverty rate, crime rate, ethnic diversity, and population density.

Going from an area with zero diversity to an area with maximum diversity would be predicted to lower trust by .14 points on a 4 point scale. (Diversity has a minimum of .25) By contrast, going from maximum to minimum poverty increase trust by .66 points.

What this implies is that the net effect of high SES individuals who increase local levels of diversity could easily be positive with respect to social capital.

It’s also worth noting that Putnam’s entire model, all these variables combined, only explained 26% of the variation in trust between people.

Replicating Putnam

A meta-analysis of attempts to replicate Putnam’s finding found that most replications failed.

For a variety of reasons, this isn’t a very well done meta-analysis. From a race realist perspective, one salient problem is that it doesn’t look at the moderating influence of different categorizations of ethnicities, and the measures of diversity utilized aren’t sensitive to the differences in genetic distance between pairs of ethnic groups. So, a study in this meta-analysis might count a half black and half white area as being just as diverse an area that is half Scott and half Irish.

But the US replication rate is only 50%, and US studies typically use simple racial (rather than ethnic) categorization schemes, and so are typically not open to this line of critique.

Another problem with this meta-analysis is that studies finding an adverse effect of ethnic diversity on trust would be counted against Putnam’s hypothesis if the effect wasn’t statistically significant. A better way to bin these studies would have been on the basis of the direction and significance of the effects. The way this review was done leaves open the possibility that most of the failed replications produced findings that are in the direction that Putnam’s study would predict. If that is so, this increases the probability that Putnam’s result is real.

(It also isn’t clear to me that standard significance testing is appropriate in regional analyses. Also, “vote counting” meta-analyses are inherently kinda crappy.)

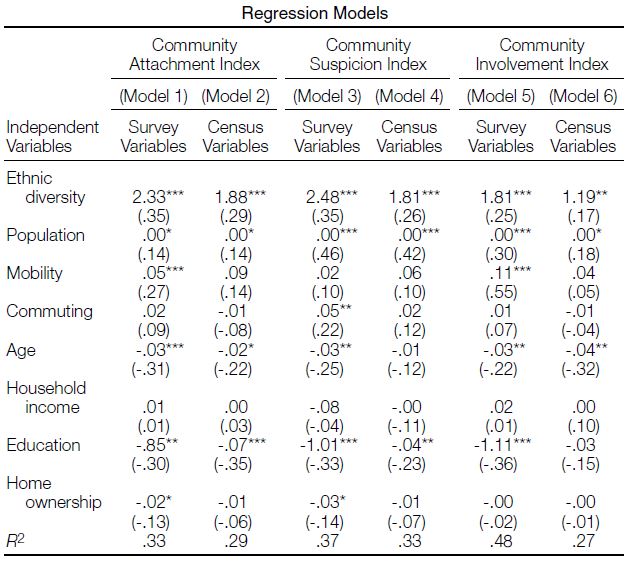

I recently decided to take a closer look at the US studies that were counted as successful replications. Specifically, I was interested in seeing if the absolute effect of diversity was ordinarily weak in multivariate analysis, if the proportion of variance explained by the total model was usually small, and if the impact of SES normally remained significant as well. Seven of the successful replications proved open to this sort of analysis.

Fieldhouse and Cutts (2010) look at both subjective ratings of trust in an area and objective participation in voluntary associations. Diversity is found to have a smaller effect than poverty in the US, though the same was not true in the UK. That being said, the impact of diversity in the UK was only significant for one of two measures of social capital.

Guest et al. (2008) looked at 3 measures of social capital. While diversity had a statistically significant effect in a multivariate model, it explained less than 1% variation in various measures of social capital.

Alesina and Ferrara (2000) utilized an ethnic diversity measure based on 35 ancestry categories and a racial diversity measure based on 5 ancestry categories. Social capital was measured via participation in voluntary associations like churches, unions, professional/hobby clubs, etc.

Before controlling for confounding variables, racial and ethnic diversity had significant relationships to association membership but these correlations were extremely weak.

Race and SES variables remained significant in the multivariate model which itself only explained 9% of the variance.

Lipford and Yandle (2009) find that a 10% increase in diversity raises volunteerism by 1 per 100 people. A 10% increase in people with a college degree increases volunteerism by 5-6 people per 100.

Dincer (2011) calculated racial diversity based on 6 ancestry categories. Diversity was found to have a U shaped relationship with trust, with trust peaking when diversity equals .34.

Other variables were found to have a linear relationship with trust. A 10% increase in the proportion of people with college degrees predicted a 10% increase in the proportion of people who have a high level of trust. A 10% decrease in income inequality predicted a 15% increase in trust. Etc.

The proportion of variance explained by Dincer’s models was very high, around 80%, but this is probably because he was comparing states rather than more disaggregated geographical units.

Stolle et al. (2008) found that having lots of neighbors of a different race lowers trust. This effect is much weaker among people who actually talk to their neighbors.

In total, Stolle et al’s model explained 12% of the variance in trust. Standardized effect sizes aren’t presented, but education’s effect has a lower p-value.

This interaction with talking to your neighbors might mean that anti-social people are more negatively impacted by diversity. It could also mean that when diversity increases and the new neighbors are crappy people don’t talk to them but when their new neighbors are good they do talk to them.

Rice and Steele (2001) looked at how ethnic diversity related to social capital in Iowan towns. They found a negative relationship between diversity and various measures of how well a community is liked by people who live there. Diversity’s independent effect is similar to that of education, and the total model explains around 35% of the variation in social capital.

Ironically, this is an exception to the rule that says that US studies measure racial diversity. This was a true measure of ethnic diversity, and the sort of difference measured here, across towns in Iowa, reflects towns with varying levels of Americans with German, French, English, Irish, etc., ancestry.

There are two studies not included in the meta-analysis of Putnam replications that I think are worth adding to this mini-review.

Alesina and Ferrara (2002) looked at the relationship between racial diversity, ethnic diversity, and income inequality, with trust. Income inequality and racial diversity each correlated weakly at -.1 with trust, while ethnic diversity correlated even more weakly at -.03.

In the multivariate model, racial diversity had a significant effect while ethnic diversity and income inequality did not. The reported effect sizes aren’t in a format that can be compared, but median household incomes effect was also significant and had a lower p-value than the effect of diversity. The total model explained 11% of the variation in trust. Obviously, racial diversity could not have contributed much of that since its bivariate relationship with trust only explained 1% of the variance.

Finally, Kikergaard (2017) analyzed data on 3,100 US counties while looking at how ethnic diversity related to a county socioeconomic status. This analysis found that the relationship between ethnic diversity and SES goes away after controlling for cognitive ability.

I also ran my own analysis looking at how variation in national life satisfaction was predicted by ethnic diversity. I used data on life expectancy, life satisfaction, and national wealth from the 2016 World Happiness Report, data on ethnic diversity from Alesina et al. (2003), data on IQ from Lynn and Vanhanen (2012), and national wealth data from the World Bank.

At first glance, there was a moderately strong negative relationship.

Controlling for IQ reduced this effect to zero:

Controlling for national Wealth reduced the effect of IQ, suggesting that ethnic diversity negatively correlates with national IQ which in turn lowers national life satisfaction by inhibiting economic growth.

I have three takeaways from this mini-review of Putnam-like studies, which was obviously biased in a way that would inflate the effect of diversity:

- There is a very high probability that ethnic diversity has, at most, a small effect on social capital. This effect is statistically significant in studies with huge samples, but it is not practically significant.

- It is moderately probable that SES has a larger effect than ethnic diversity.

- We don’t know what explains most of the variation in social capital across regions or individuals. (And that’s true even if you add in genes to the mix.)

The Harvard Trust Experiment

After Putnam’s research, the most often cited on diversity and trust is Glaeser et al. (2000). This paper involved 198 students from Harvard playing an economic game that experimentally measured trust.

One player, the sender, is given some amount of money. They then chose some portion of that money to be sent to a second play, the recipient. The recipient’s cash is then doubled and they can return as much of the money as they want to the sender. The more a sender trusts the recipient to fairly compensate them, the more money they will send.

Glaeser et al. found that in multiracial pairs of students the sender sent less money and the recipient sent back less money. This finding is particularly striking because the multi-racial pairs consisted of Whites and Asians, who don’t have the same history of racial conflict as Whites and Blacks, and because everyone involved was a high SES, highly intelligent, young, ivy league college kid.

At least, that is how the study is normally presented. In fact, none of these effects were statistically significant. In other words, they were weak enough to easily occur simply due to sampling error. (And this is before correcting for multiple testing!). The statistical significance of a result is a significant predictor of the likelihood that it will replicate, and, on average, findings require a much lower p-value than what is seen here before they hit a 50% replication rate.

Even more egregious, the adjusted r-squared values for the sending models are actually negative. The model for money sent back is better, it explained 15% of the variance in return behavior, but, again, the diversity variables are not significant.

In any other context, a small sample study that failed to produce statistically significant findings would be interpreted as either useless or as evidence against the existence of an effect. Treating it as evidence for an effect is not justified.

As was the case with Putnam’s paper, looking at other research trying to experimentally tease out the effects of diversity doesn’t seem to help the anti-diversity case. For instance, Nai (2018) reported the following:

“Study 1 found that people residing in more racially diverse metropolitan areas were more likely to tweet prosocial concepts in their everyday lives. Study 2 found that following the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, people in more racially diverse neighborhoods were more likely to spontaneously offer help to individuals stranded by the bombings. Study 3 found that people living in more ethnically diverse countries were more likely to report having helped a stranger in the past month. Providing evidence of the underlying mechanism, Study 4 found that people living in more racially diverse neighborhoods were more likely to identify with all of humanity, which explained their greater likelihood of having helped a stranger in the past month. Finally, providing causal evidence for the relationship between neighborhood diversity and prosociality, Study 5 found that people asked to imagine that they were living in a more racially diverse neighborhood were more willing to help others in need, and this effect was mediated by a broader identity.”

Something more closely approaching a replication of Glaesser’s paper comes from Jiro (2009) who writes: “We show that the level of trust and reciprocity in an intercultural trust game experiment between Austrian and Japanese subjects differs from the results of an intracultural experiment run in the respective countries among compatriots. Austrian subjects show significantly higher levels of trust towards Japanese subjects than towards fellow countrymen. Japanese do not differentiate between Austrian or Japanese subjects. Japanese subjects are found to be less reciprocal than Austrian subjects. ”

So far as I know, there isn’t a meta-analysis of these results. However, Jonhson and Mislin (2009) meta-analyzed the relationship between the results of a trust game experiment and how ethnically diverse the country in which it was conducted is. They found a meta-analytic effect size that was statistically insignificant and positive for trust, meaning that people tended to send more money in more diverse nations.

However, there was also a significant negative effect of diversity on trustworthiness, meaning that in more diverse nations people tended to send less money back.

The same was true of income inequality. A one-third standard deviation decrease in trustworthiness was predicted by a one standard deviation increase in either diversity or income inequality. Unfortunately, they didn’t test both variables at once so that we could see the effect of each variable after controlling for the other.

This result suggests that diversity doesn’t lead to less trust, and its effect on trustworthiness might be offset by economic effects. It’s not strong evidence one way or the other though since the diversity of a nation might not be a great predictor of the diversity of pairs of people in the studies conducted there.

Now, it is very interesting that a later version of this paper, Jonhson and Mislin (2011), doesn’t mention ethnic diversity at all. Instead, it reports these results by regions and finds that Africa scores far lower than other regions on trust and trustworthiness.

I suspect this is because the diversity effect was confounded by the fact that Africa is extremely ethnically diverse. This makes me inclined to suspect that there was no effect for diversity qua diversity, though obviously, that is just speculation.

Another relevant experiment comes from Finseraas et al. (2016) who looked at soldiers who were randomly assigned roommates and later completed a trust game. They found that those from highly diverse areas exhibited less trust in immigrants, but those who roomed with immigrants exhibited more. I am inclined to interpret this as suggesting that the immigrants out in society may have been the sort of people, based on individual characteristics, who lower trust, while the military may force people to act in ways that are less problematic.

Longitudinal Research

Now that we’ve reviewed experimental and cross-sectional research on this question, let’s turn to longitudinal studies.

First, Williamson (2008) reports on how social capital and race relations changed in Lewiston, Maine, between 2000 and 2006. Lewiston received a large influx of Somali refugees during this time period, decreasing the proportion of the town that was white by 7%. Changes in social capital and race relations were compared with what occurred during the same time period in Auburn, Maine, a city from the same county that was similar to Lewiston across a wide range of variables in 2000 and which did not receive an influx of immigrants. Despite these immigrants being both racially different, and poor, the two cities did not significantly differ in how their levels of social capital or inter-racial relations changed, although anti-immigrant attitudes did rise more in Lewiston.

Second, Ziller (2015) analyzed changes in trust in 22 European countries between the years 2002 and 2010. Cross-sectionally, nations with higher levels of ethnic diversity and non-Western immigrants had lower levels of trust. However, changes in these variables did not predict changes in trust over time.

Longitudinal changes in general immigration levels did, suggesting an effect of immigrants qua immigrants, regardless of race. However, this effect was only negative when the economy was not growing. At levels of economic growth above zero, the effect of immigrants on trust was positive and statistically insignificant.

Finally, Laurence and Bentley (2015) conducted a longitudinal analysis looking at how changes in an English community’s ethnic diversity predicted changes in social cohesion. In the first place, it found that diversity and economic variables both mattered. More interestingly, it found that the adverse effects of diversity were much stronger among those individuals who, over the course of the study, had decided to move to a more homogeneous area. By contrast, there was no effect for diversity among those who chose to move to a more diverse area.

In sum, the longitudinal literature I’ve been able to find doesn’t seem to compelling support the idea that diversity qua diversity has a negative impact on social cohesion, and suggests that the effects it does have will be conditional on society-wide factors like economic growth and individual factors relating to the people who experience increases in diversity.

One potential individual-level factor that moderates a person’s response to diversity is their political ideology. Laurence et al. (2018) found that diversity only lowers trust among those who view the relevant outgroups as threatening to begin within a sample of English participants. Assche et al. (2018) found basically the same thing in the Netherlands. Of course, it might also just be that individuals who are likely to negatevly react to diversity and also, and maybe even consequently, more likely to adopt anti-immigration viewpoints.

In conclusion, I don’t think the social-scientific literature I am aware of has compellingly shown that diversity qua diversity has an important effect on social cohesion. With respect to immigration, this literature seems to imply that high SES immigrants would probably increase local social cohesion even if they also increase levels of ethnic diversity.

Can you explain how you got the 0.04 number for the Putnam study? I had my statistics teacher look it over with me and you must’ve done some equation to get it; none of the numbers on the chart you show would give the usage of the number you’re explaining.

LikeLike

Pingback: Race, IQ, and the State of Nations | Rightwingism

Reading the Nai study it seemed to be very subjective and largely relative to the cultural expectations. Tweeting Prosocial is more about appearing a good person than being one.

Study 4 seems to come conclusion drawn from different concepts where it cites study 3 relating to diverse countries then attributes it to diverse neighbourhoods. Identifying with “humanity” is a subjective definition that doesn’t relate to any sense of goodness and appears completely arbitrary as a means to associate diversity with prosocial tendencies.

The last study is people telling you what they think you want to hear rather than what they would actually do. If the culture wasn’t as it was they would tell you something else. Because we live in an anti-racist society if you give people an imaginary situation where they are surrounding by diversity then they will they you they are going but that doesn’t mean they will. For instance if you ask chinese people the same question they would give you the same answer, they would tell you want was socially acceptable to say.

LikeLike

Pro-immigration, pro-diversity lunatic you must be. Here’s the thing: I personally don’t care if high SES immigrants may (they don’t, that’s laughable) increase “social cohesion”. All of these studies are stupid to me, expecting people to be honest, especially White people, on how they truly feel about racial diversity is useless. Most are going to lie, or most are just simply brainwashed. You see, how does this explain “White flight”? I believe the fact that Whites engage in this proves that they want to be left alone, live among each other, even if it’s sub-conscious and they still pretend to be “anti-racist” and “pro-diversity”. And we know they do pretend to be these things based on what they believe; anti-hate speech, pro immigration, pro amnesty, etc. Going over your blog, it seems that you are Pro-White, yet you are shilling racial diversity, of course, only if they are “high SES” individuals. Sounds a bit subversive, I must say, a bit “civic nationalist”. I swear, sometimes data nerds are just insufferable. The *enemy* conducts the vast majority of these studies, and they have no problem falsifying data to push “muh diversity muh strength” narrative. In fact, they do it all the damn time. Sorry, I just don’t trust them. And the fact that you feel the need to “critique” at least SOME of the data that solidifies our talking points and beliefs is rather pathetic, and I can only assume that you are intentionally muddying the waters.

LikeLike