Much has been written recently about Schulz et al. (2019), a paper which argues that the Catholic church made the West less conformist, more individualistic, and more open to outsiders by insisting that people organize into nuclear families rather than larger kin networks, and by demanding that people never marry their relatives. In this post, I aim to summarize this paper and defend the claim that these changes were brought about in part by genetic changes to Western populations that these church policies caused. I’ll also argue that the mechanisms described by Schulz et al. surely impacted the IQ of western populations as well even though the paper does not directly address this.

To begin with, the paper provides a fairly concise summary of the Church’s policies concerning marriage which is worth quoting:

“By the Early Middle Ages, the Church had become obsessed with incest and began to expand the circle of forbidden relatives, eventually including not only distant cousins but also step-relatives, in-laws, and spiritual kin… the Church promoted marriage “by choice” (no arranged marriages) and often required newly married couples to set up independent households (neolocal residence). The Church also forced an end to many lineages by eliminating legal adoption, remarriage, and all forms of polygamous marriage, as well as concubinage, which meant that many lineages began literally dying out due to a lack of legitimate heirs… by 1500 CE (and centuries earlier in some regions), much of Europe was characterized by a virtually unique configuration of weak (nonintensive) kinship marked by monogamous nuclear households, bilateral descent, late marriage, and neolocal residence”

These cultural pressures are contrasted with those that predated them. The authors cite various historical accounts which claim that the emergence of agriculture favored people organizing into tightly nit groups which distrusted outsiders and featured a great deal of respect for authority. Because of this, people living together in large family units was ideal.

To empirically assess the effect of church policies on the Western mind, the authors assembled data on 24 psychological and sociological variables which can broadly be grouped as measures of individualism, conformity, and pro-sociality.

Individualism’s theoretical connection to family structure is obvious, if society is organized into large kin networks then people will associate based primarily on family identity whereas a society organized around the nuclear family will necessitate people associating with others on the basis of individual characteristics. Of course, this means that people in a nuclear-family based society will need to get along well with people they are not related to and so this will select for pro-social behavior and even altruism. The tight knit kin networks of early history also meant people lived within the context of familial hierarchies meaning that respect for authority, tradition, and conformity, would be culturally selected for. The breakdown of this mode of organization would therefore be expected to select against these things.

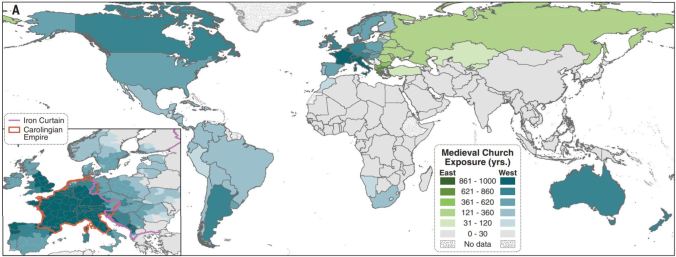

These psychological and sociological variables were then related to a measure of church exposure, and a measure of kin based organization. At the national level, the measure of church exposure was based on the number of years a nation was under the sway of the Catholic church prior to the year 1500. There was also a sub-national analysis of 440 regions within Europe which measured church exposure based on the number of years a given location had a bishop’s office within 100 km of its center.

Both church exposure and the socio-psychological variables were also related to a Kinship Intensity Index constructed from data on rates of cousin marriage, polygamy, co-residence of extended families, clan organization, and community endogamy.

In the national analysis, both Kinship Intensity and exposure to the Catholic church were shown to be very good predictors of the socio-psychological variables in a way that exposure to the orthodox church was not. It was also shown that cousin marriage on its own was often a better predictor of these outcomes than was the entire Kinship Intensity Index.

It is worth noting that these relationships are extremely strong with church exposure or cousin marriage predicting the majority of variation in several measures of individualism and pro-social behavior.

And church exposure itself correlated extremely well with cousin marriage rates (Spearman correlation = .82). Specifically, they find that an additional 500 years of church exposure predicts a 1.2 SD decline in the KII and a 92% reduction in cousin marriages.

All these associations are shown to persist after controlling for “(i) parasite stress and tropical regions, (ii) irrigation potential, (iii) suitability for oats and rye, (iv) time since the origins of agriculture and genetic heterogeneity (expected heterozygosity), (v) major religious traditions (e.g., Catholicism, Protestantism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, etc.), (vi) religiosity, and (vii) continental fixed effects”. Thus, these findings cannot be explained by parasite based theories of collectivism, Jared Diamond type explanations of civilizational development, or broad notions of race.

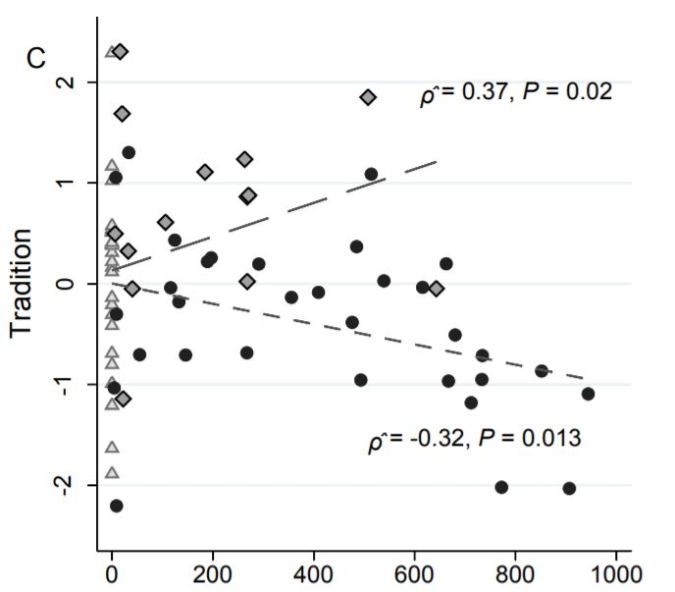

In their main regression model, each additional century of church exposure predicts a modest increase in individualism and pro social behavior, and a modest decrease in conformity and traditionalism. The predicted effect of an additional 500 years of exposure is thus quite large.

The same basic relationships were found when looking at how variation in church exposure predicted variation in culture across 440 sub-regions of Europe.

Finally, an analysis was carried out which looked at the relationship between the psychological traits of second generation immigrants and the church history of the nation from which their parents immigrated. Across 12 tests, they find significant relationships in the expected direction in every case.

Generally speaking, exposure to the orthodox church either had no impact on these variables, or a weaker impact than did exposure to the Catholic church. An exception to this involves how people rated the importance of tradition, with catholic exposure predicting less importance attached to tradition and orthodox exposure having an equally strong correlation with traditionalism but in the opposite direction.

This is consistent with data showing the prevalence of Catholicism in a country positively correlates with the prevalence of left wing views on issues relating to sexuality and the family.

In summary, the observational data supports the central thesis of the paper at multiple levels of analysis and does so after controlling for con-founders which rule out several alternative explanations. Of course this does not prove their thesis, but this is about as strong of evidence as you are likely to get in history, a discipline which does not allow for formal experimentation.

The paper takes an agnostic view as to whether the Church’s influence on Europeans was partly genetic. They write:

“The psychological variation documented here may arise from the action of a combination of facultative, developmental, and cultural evolutionary mechanisms. It is also possible that stable institutions may favor particular genetic variants that promote success in these institutional environments. Our findings are largely agnostic regarding the relevance of these different mechanisms.

The potential genetic mechanism presented here is that the sorts of people who tend to succeed in kin based collectivist and conformist societies will differ from the sorts of people who tend to do well in more individualistic societies. For instance, if someone is predisposed to not trust strangers they may do quite well in the former society and not as well in the later one.

The authors go on to cast some doubt on this sort of an explanation writing that:

“The fact that we can detect the influence of historical kin based institutions on psychology even decades or generations after those institutions have disappeared suggests a role for inheritance, either cultural or genetic. But the fact that we can relate psychological differences among European populations to relatively recent historical events such as MFP and then explain variation even within subnational regions suggests a central role for cultural transmission””

This is a bad argument for two reasons. First, there is no reason why cultural institutions can’t produce differences between European populations. Not all population differences are at the level of race. Secondly, the amount of time that the Church has been around for is more than enough to produce significant genetic changes even in the presence of fairly weak consistent selection pressures. For instance, if the heritability of a trait is .2, quite low, and the difference in the correlation between this trait and fertility between populations is .1, then after 20 generations a difference between the populations of .4 SD will be produced. A stronger evolutionary pressure could thus obviously produce a quite large divergence in a short period of time.

The authors also fail to consider other mechanisms by which genetics might mediate the influence of the church on western psychology. For instance, societies in which people form large kin networks may lead to greater in-group favoritism simply because the in-group will consist of relatives and so helping them will be a means of spreading copies of one’s own genes.

This relates to the idea of inclusive fitness, the point of which is as follows: a genotype which makes an individual organism sacrifice its own reproductive fitness for the benefit of other organisms which also possess the same gene variant will increase in frequency across generations so long as the benefit received by the those sharing the genotype is sufficiently large. To take an extreme example, if someone dies to save the lives of four siblings, each of share shares half of their genes, then their genotype will be more common in the population in virtue of their sacrifice relative to the frequency which would have obtained if they had let their siblings die. Evolution therefore selects for a specific kind of altruism that people display towards people who are related to them and this process is called kin selection.

Kin selection doesn’t explain all forms of pro-social behavior, but it does explain a good deal of it. We know generally speaking that people act in more pro-social ways towards others the more related to them they are, this is true even when comparing how people act towards members of their own family, and that this is true even controlling for the degree of contact between people (Buss, 2019).

Though not as widely supported as the theory of kin selection, there is a view, called genetic similarity theory, which extends kin selection beyond literal families and claims that there is a systematic correlation between how well people treat others and their genetic similarity to them. Several findings lend moderate support to this view. First, we tend to be friends with people who are more genetically similar to us than we would expect if we picked friends at random. On average, friends are about as related as fourth cousins (Showk, 2014). Second, people seem to select their friends and mates so that they are especially similar in very heritable ways. For instance, Rushton (1989) analyzed data on 36 questions of political attitude, 81 questions of personality, and 12 somatic measurements, and found correlations such that friends tended to be more similar for a given trait the more heritable the trait was, and this continued to be true after controlling for similarity in education and occupation (rs of .40, .20, and .15 [ns]). Similarly, Rushton et al. (1988) found that the more heritable a mental trait was the more marital partners tended to be similar with respect to it. Finally, this sorting based may lead to better relationships. Russell and Wells (1991) found a weak tendency such that the more heritable and item was the more similarity on that item between partners predicted a happy marriage. Thus, certainly within families, and perhaps even beyond families, people tend to get along better with people as a function of their relatedness.

Of course, we all know that people display a bias in favor of their family members, even cousins and the like, and while this occasionally causes problems of nepotism arise this isn’t a huge problem because people don’t have that many relatives to be biased in favor of and because people are generally only moderately biased in favor of kin outside their immediate family.

This situation is very different in a society where large kin networks live together because this expands peoples notion of who is importantly related to them, and because they living and organizing with their relatives. This allows people to function while trusting family members and distrusting non-kin in a way that would be impossible in a less kin-based society. Moreover, in societies that allow cousin marriages people’s non-immediate family will become ever more closely related to them due to centuries of moderate incest taking place within clans and tribes.

This fact may have serious political consequences. For instance, family based corruption may be more likely when a nation is comprised of kin networks because such networks may be inclined to work in their own interest rather than the national interest. Moreover, the frequency with which people have relatives in the government who they are close with and can utilize for corrupt purposes will increase.

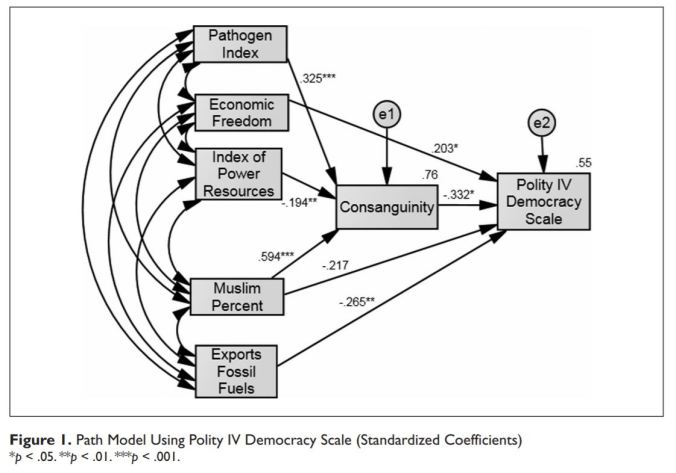

Akbardi et al. (2017) provides empirical support for this hypothesis by demonstrating roughly half of the variance in how well nations score on measures of institutional corruption can be accounted for by national variance in the prevalence of cousin marriage. This association was shown to persist after controlling for economic, ecological, and religious, variation between nations.

This kind of kin based tribalism may also inhibit people’s support for universal rights by decreasing their sense of unity with non-kin co-nationals. This intuition is supported by Rindermann and Carl (2018) who found the over a third of the variance in how well nations up hold human rights can be accounted for by variance in national rates of marriage between cousins.

Moreover, the findings of Woodley and Bell (2012) showed that the negative correlation between the prevalence of Islam in a country and a nation’s score on measures of democratic values is largely accounted for by Islam’s association with national rates of cousin marriage. Cousin marriage itself had a direct effect on democracy which was stronger than the effect of economic freedom.

Note that this mechanism of kin selection doesn’t require that the frequency of any genes be changed and so is independent of the selective pressures argument that the paper argued (poorly) against. That being said, these two mechanisms work together in the sense that helping your kin will be even more helpful in societies where they are your primary associates and so this will be selected in favor of via natural selection.

Perhaps more importantly, the authors totally ignore that the church’s huge effect on cousin marriage rates would also have a huge impact on the rate of inbreeding depression within regions. To westerners this may seem like a non-issue, but there are many parts of the world in which even today more than a third of marriages are between cousins.

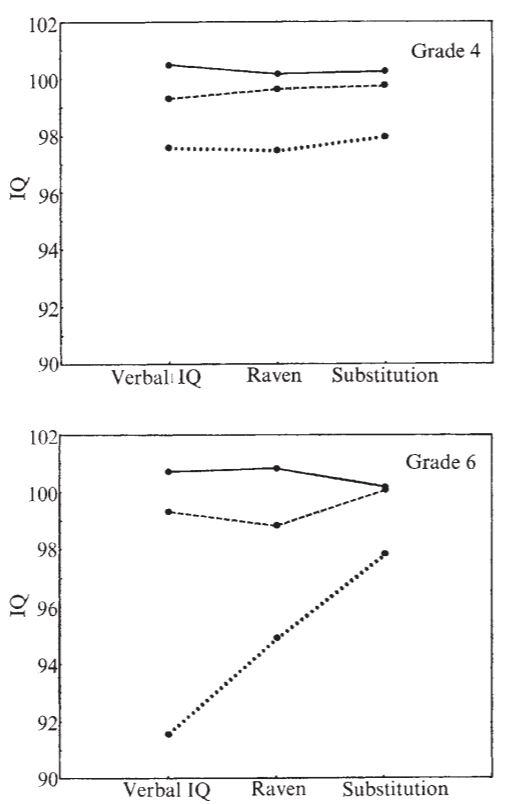

This consideration also makes it obvious that the catholic church, via its removal of cousin marriages, increased the genotypic IQ of Western people. After all, it is non-controversial that repeated generations of cousin marriage genetically impacts the way people’s minds work in a way that inhibits intellectual functioning and empirical tests support this premise. For instance, Bashi (1977) analyzed data on 3,203 Israeli and Arab children and found moderate IQ gaps between non-inbred children and the children of first cousins, and very large gaps between non-inbred children and the children of double first cousins (children whose parents are themselves siblings).

Badaruddoza and Afzal (1993) reported data on 100 Indian children and found an 11 point gap between the non-inbred children and the children of cousin marriages.

And Fareed and Afzal (2014) report even more extreme results in a study of 408 Indian children (each row down is ever more inbred):

The impact of inbreeding on group differences in intelligence was empirically evidenced by Rindermann and Carl (2018) who found that national cousin marriage rates had a direct negative effect on national IQ scores and an indirect effect via depressing formal education levels.

With respect to Christianity, the paper found that some of its effect on democracy and measures of rights could be explained by its impact on cousin marriage rates, but not all.

Further evidence for a role of historic inbreeding in group differences is provided by Rushton (1989) who found that the more harshly a given cognitive ability was impacted by inbreeding the more black and white Americans differed on that cognitive ability.

There has been less research into how inbreeding effects other aspects of the mind, but it surely does since the regions of the brain implicated in intelligence are also utilized for many other psychological functions. One study worth noting is Berner (2017) who found that a multitude of psychological pathologies were more common in inbred children (N = 2,000).

Thus, there is reason to think that the church’s impact on cousin marriage rates may have genetically impacted Western people’s minds in even more ways than I have suggested. The totally contrary position, that groups don’t differ at all with respect to the genetics of psychology, entails either that groups have not historically differed in rates of inbreeding, or that inbreeding does not impact people’s psychology, both of which are totally unbelievable statements. And so a key take away from this paper not stated by its authors is that it provides evidence of a cultural history which can we confidently say probably produced genetic differences between groups for traits of social, political, and economic, importance.

Why then Catholic countries (Italy, Portugal etc.) have a greater incidence of cousin marriage than Protestant ones?

Unrelated: If you haven’t yet, watch Gad Saad chatting w/ David S. Wilson – they talked a little bit of THIS paper and W.E.I.R.D. psychology (which they made clear: it’s “Western”, not “White”!); many points, I think, you’d disagree and that could be made into a neat video! 🙂

Yours sincerely,

LikeLike

I’m sorry, here’s the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zXcU6qPcVvE

LikeLike

Protestants are super-Catholics by this logic: remember, Luther was complaining precisely that the Church is weighed down by corrupt traditions and needed to return to pure spiritual matters detailed only in scripture — a highly analytical and rationalistic take on Christianity. Protestant countries are also the most individualistic, being the birthplaces of modern capitalism and the industrial revolution. One could argue that the Catholic religion first introduced selective pressures towards individualism and after several generations, when the population gene pool and the hence the resultant psychological profile of the people had changed enough, they abandoned Catholicism itself as overly “traditionalistic” and outmoded, suitable for a less individualistic time. Of course, not long after, Protestantism itself was thrown overboard and replaced with the lay faith of secular progress.

LikeLike

Hello! Lovely article as always, great that you are back! 🙂 With Christmas right around the corner would it be possible for you to put together a recommended readings list? Maybe just take your 10 or 20 favourite books ? Would be great to be able to read some myself and also get as gifts for friends and family! 🙂

LikeLike

Not convinced it increased IQ. I think Dr. Woodley said in a Molyneux interview, analyzing Iceland, that marrying one’s 3rd cousin gave the best results. I am also reminded of Darwin, whose children were at least not of low IQ, three sons even members of the Royal Society. Kierkegaard’s father married his 3rd cousin, and the brain power of the Kierkegaard’s is well documented. I’d say Kierkegaard was one the greatest thinkers who ever lived.

LikeLike

“This consideration also makes it obvious that the catholic church, via its removal of cousin marriages, increased the genotypic IQ of Western people. After all, it is non-controversial that repeated generations of cousin marriage genetically impacts”

No, this is conceptually wrong. You are missing the mechanism and getting the population genetics wrong. Inbreeding depression and hybrid vigor are single generation effects.In a small breeding pool the same recessive defects are more likely to match up, be expressed and eliminated as the offspring with these traits are less fit. In a large breeding pool, these defects still occur but will accumulate over generations until there are so many recessive defects that they finally start to match up and be expressed.

LikeLike