When discussing the prevalence of discrimination, those calming that discrimination is rampant sometimes appeal to their “lived experience” as evidence for their view. Moreover, if statistical evidence is marshaled which suggests that discrimination is not prevalent, some people will take offense and claim that you are invalidating their lived experience.

Traditionally, this kind of thinking is called “anecdotal reasoning” and people learn that it is problematic sometime in high-school or early college. Generally, it is said that anecdotal reasoning is to be avoided because human memory is fallible and because an individual’s experience will often differ from the experience that is typical. For these reasons, while personal experience can be useful in the formulation of hypotheses, statistical evidence is preferred when it comes judging the truth of such hypotheses. When better evidence isn’t available, and personal experience is all we have, we should either avoid forming a view, or hold the view we form with a great deal of uncertainty.

This is all true and applicable to people’s lived experience of discrimination. But there are even deeper problems here. Often, there is no evidence that discrimination took place in people’s recollections of their “lived experiences” even when those experiences are taken at face value. Frequently, these experiences merely consist of a minority member being treated in a way they don’t like by a majority member. For instance, a video recently went viral in which a white police officer unfairly harassed a black male.

This was deemed by many to be an instance of racial profiling even though the video contains literally no evidence to suggest that race was a motivating factor. All you have is a white person being an jerk to a non-white person. But lots of people are jerks. White people are sometimes jerks to fellow white people and sometimes jerks to minorities. Because of this, we cannot assume that the motive for a white person being a jerk is race whenever the person they are being a jerk to is non-white. The more parsimonious explanation is that there is a general motivation for being a jerk which can account for both instances, and we should not assume otherwise unless we have good reason to do so.

A particularly stupid and high-profile example of this comes from the media’s coverage of Trump. NPR and similar left wing organizations run headlines like “Low IQ,’ ‘SPECTACULAR,’ ‘Dog’: How Trump Tweets About African-Americans” suggesting that when trump calls Black people things like “low IQ” he is doing so because of their race. This is dumb, as Trump calls lot’s of people these names. By chance he’s in the news this week for calling fellow white man Joe Biden low IQ. The reason Trump makes fun of black people who don’t like him is probably the same reason for which he makes fun of white people who don’t like him. Certainly, there is nothing in the “lived experiences” of black people Trump has made fun of which suggests otherwise.

This sort of fallacious thinking isn’t unique to those who take a left wing perspective on race. Consider the following account Coleman Hughes gives of an instance in which he experienced racial discrimination:

“I was in the Writing Center at Philosophy Hall, waiting outside my professor’s office while he finished meeting with another student. As I sat there wearing a plain white tee, ratty black jeans, and a pair of worn leather shoes with mismatched laces, I noticed a pair of eyes glaring at me from across the room. Eventually the owner of those eyes walked over and asked, with barely concealed suspicion, “Who are you here to see?” I said my professor’s name and pointed to his office. But my answer didn’t seem to satisfy the man, so he entered the office and spoke with my professor to verify that I was telling the truth. No other student in the Writing Center was subjected to any scrutiny whatsoever.”

This is similar to the following from John McWhorter:

“I have been discriminated against because of my color twice in the past year. At a doctor’s office, I was in line in front of the white female receptionist’s desk. She handled two white men ahead of me with dispatch. Then when it was my turn she looked at me and then quietly looked down to riffle through some papers. This continued for about 30 seconds. Finally, I said “Miss?” and she looked back up, still paused, upon which I said “I’m here for an appointment,” upon which she realized her mistake—“Oh …!”—and took care of me. But why did I need to summon her that way? Because she made a spot, subconscious assumption, based on my skin color and likely the fact that I wasn’t wearing business clothes, that I was the help of some kind. Or, at least, not a patient. Classic microaggression.

The latest one was when I actually was wearing business casual, having entered a corporate office one evening to teach a night class on philosophy to some Columbia alumni. The receptionist—again a white woman about 32—smilingly asked me if I was “tech.” In other words, she assumed I was there to get the projector set up and so on, as opposed to my being there to, well, teach the class. Golly, I wonder what made her think that?”

These authors both take fairly conservative positions on racial issues, and think that America is less racist than many liberals do, and so it is noteworthy that even they interpret their interactions this way.

Now, these anecdotes are stronger than the first two examples I pointed to because they involved black people being treated differently than white people who are near by and acting in a similar manner. But it is still invalid to infer from these experiences that racial discrimination was taking place. After all, McWhorter and Hughes may have in fact differed from the near by white people in a way that they did not notice and this may be what caused them to be treated differently. Certainty, I have had experiences similar to the ones they recount when interacting with other white people. I’ve been ignored in lines before, I’ve had people false assumptions relating to jobs I was or was not doing, and I’ve had people be suspicious of my reasons for being places. I don’t know what the causes of these incidents were, but it surely wasn’t race, and I see no reason to assume that whatever motives white people have for occasionally treating me and other white people in these ways are not also what has motivates white people to occasionally treat black people in these same ways. Again, a non-racial motive is the more parsimonious explanation and so should be preferred until there is evidence against it.

Now, these examples were fairly innocuous, but sometimes they are not. Concerning encounters in which harassment or violence takes place, there are sometimes obvious plausible explanations for why the minorities in the situation might have been treated different from the whites that don’t involve any kind of unproved aggression.

But let’s assume that they do involve unproved hostility. In addition to what I’ve already said, I’d add the following: when people decide to be assholes, they have to chose a victim. Even if the aggressors in such incidents pick their victims totally at random, in a nation as large and racially diverse as ours there will be a significant number of incidents in which black people will be chosen as the victims when white people were available as potential victims as well. Thus, we should expect that, on occasion, a black person will be victimized for doing something that near by white people are also doing, even in a totally non-racist society. A collection of such anecdotes therefore cannot be used as evidence against the notion that we live in such a non-racist society.

Now, there are examples of the opposite occurring, where white people are victimized by black people when black people could have been victimized just as easily. Consider murder. Every year, there are about one thousand incidents in which a black person murders a white person. This is far greater than the roughly 350 white on black murders that occur annually.

In many of these cases, the black murders probably could have murdered a black person instead of a white person. Indeed, black murders do select black victims the vast majority of the time.

Now, many of these stories could be made into a news story. We could have had a black-on-white Trayvon Martin story every month of every year for the last 50 years. And we could have assumed that the motivation of such murders was race on the basis of no evidence outside the fact that they involved black people mistreating white people.

In fact, this inference would be more rational than the reverse. There are experiments in which people are assigned to two groups which consider an identical situation other than the race of a person involved in said situation. One group is assigned to a situation with a white character and another group is assigned to an otherwise identical situation with a black character. Participants and then asked various questions, such as how responsible the hypothetical person is for negative events that happen to them, whether they would support a hypothetical politician, whether the hypothetical person deserves help, etc. Zigerell (2018) meta-analyzed 17 such studies and found that white people exhibited a statistically insignificant tendency to favor black people while black people exhibited a pro black bias that was larger and statistically significant.

We see similar results from Mitchell et al. (2005). This paper analyzed data from 34 studies in which people acted as jurors and voted on whether a given defendant was guilty and, if so, what their sentence should be. These experiments compared the recommended verdicts and sentences for defendants that were identical in all ways other than their race.

For verdict decisions, white participants exhibited no practically significant bias while black participants exhibited an in-group bias equivalent to a .43 standard deviation difference in treatment based on race.

With respect to sentencing decisions, we once against see basically no discrimination among white people and a pro-black bias among black participants equal to an absurdly strong .73 standard deviations.

Thus, experimental evidence suggests that black people are far more likely than white people to engage in discriminatory behavior. Nonetheless, when black people treat white people unfairly we usually don’t assume that it is because of our race without specific evidence suggesting that this is so.

This different in interpretation arises because we have different theories which we use to interpret and color our experience. Such theories can lead to dramatic errors. Kleck and Strenta (1980) conducted a set of relevant experiments demonstrating this. In them, study participants were assigned a negative physical attribute. Some were given fake scars by make up artists while others had to fill out a biographical saying that they had epilepsy. These subjects then interacted with other people who were given said biography cards. Study participants reported that people liked them less, were patronizing, and tense, because of their assigned physical defects. What the participants didn’t realize was that the people they were interacting with were not actually informed about their supposed epilepsy and a moisturizer that was applied to their scars after they viewed it in a hand mirror was actually a product that erased the whole thing. Thus, they perceived the discrimination they expected, even though none was actually taking place.

The flawed nature of how many black people have been socialized to view society is evidenced their perceptions of discrimination in contexts where they could not plausibly know whether or not discrimination is taking place in virtue of their lived experience.

For instance, Gallup runs a poll asking people the following question: “If two equally qualified students, one white and one black, applied to a major U.S. college or university, who do you think would have the better chance of being accepted to the college — [ROTATED: the white student, the black student] — or would they have the same chance?“

In total, 61% of black Americans think that the white student would be discriminated in favor of in such a scenario while only 5% think that the black student would be discriminated in favor of. In reality, black students would be roughly 21 times as likely as a white student to be admitted in such a scenario.

This tells us that black people endorse a model of society which paints it as being far more anti-black, and less pro black, than it actually is. Given this, we should expect that black people will over-interpret unpleasant incidents with white people as having racial motivations just as anyone else would who endorsed such a mistaken theory of society

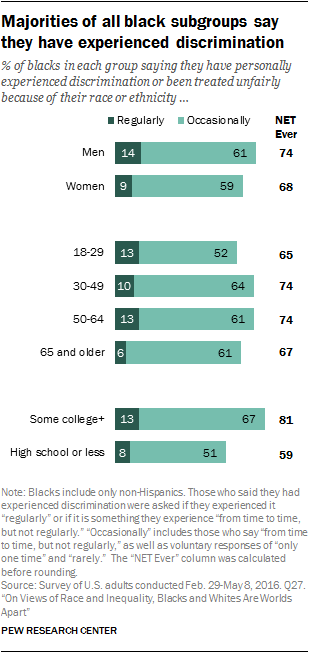

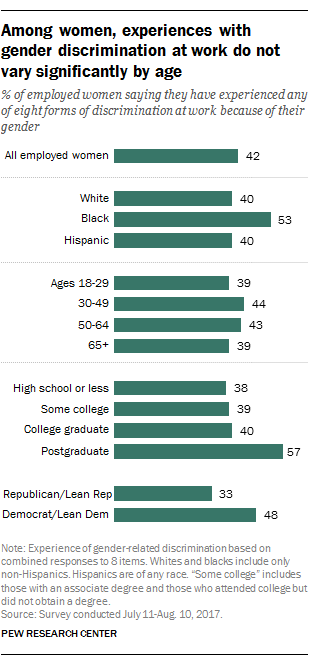

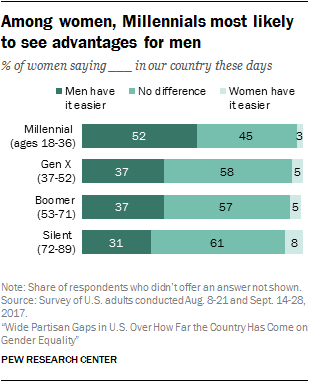

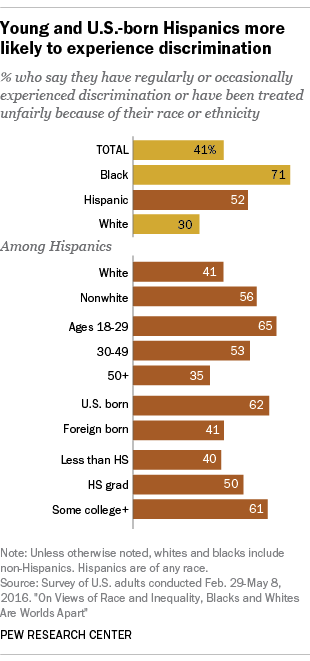

Finally, I want suggest that survey data on personally experienced discrimination attests to their lack of validity because the people who say that they have experienced the most discrimination are not the people who probably actually have, and are instead the people who we might expect to be most influenced by leftist ideologue.

The first variable fitting this pattern is age. Society has become less sexist and less racist with time. Because of this, old people should be the most likely to report having experienced significant discrimination. Instead, the data suggests that old people are the least likely to report having experienced discrimination, with middle aged people being the most likely. Young adults report lesser levels of discrimination that middle aged people, but rates equal to or higher than very old people, and will probably report record levels of discrimination by the time they reach middle age.

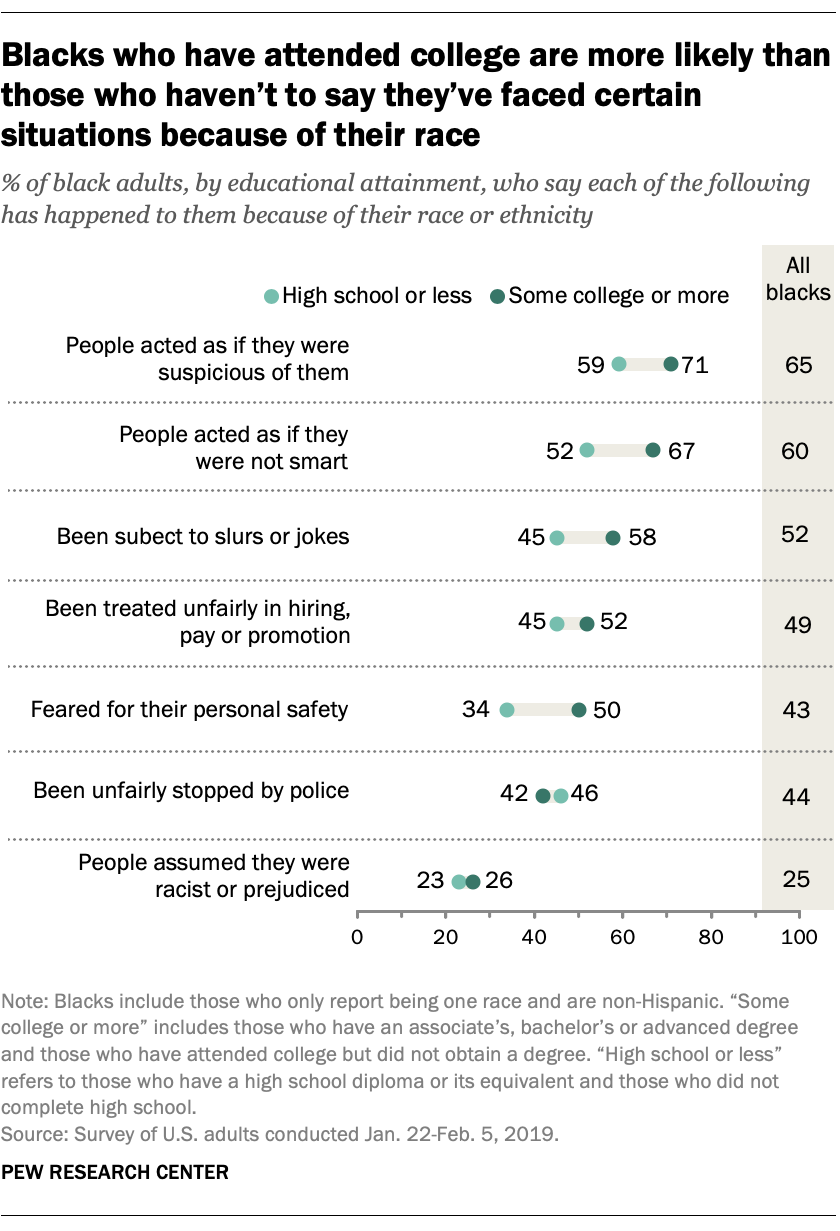

The second important variable is education. People who are uneducated, and so live in poorer conditions among people who have relatively non-progressive values, should be the most likely to experience discrimination. But what surveys suggest is that those with college degrees are the most likely to report having experienced discrimination.

Both these patterns are present in self reported discrimination among women, Hispanics, and blacks, and both patterns are predicted on the basis of exposure to “woke” political ideology.

It is also noteworthy that black people are more likely to report having been discriminated against if they live in a black-majority area. This too is easily explainable in terms of the spread of ideology, but not what you would expect if these reports accurately reflected actually discrimination.

We generally don’t accept anecdotes as evidence. We shouldn’t change this norm when anecdotes are called “lived experience”. Aside from the inherently problematic nature of anecdotal reasoning, people’s experiences of discrimination often involve makes fallible inferences about the motives of others and we have good reason to think that people’s expectations can heavily influence such inferences. Moreover, the people who report being the most victimized by discrimination are exactly the people we would expect to if self reported discrimination was the result of ideology rather than genuine victimization. Of course, none of this implies that discrimination never happens, but it does imply that personal experience often cannot be taken at face value, and so we should not use people’s purported experiences with discrimination to asses the degree to which people in our society experience actual discrimination. In other words, we should not take seriously the idea that lived experience is actual evidence.

I must say, after reading around on this site a bit, I do like the lit review method. Every good scientist knows that you should simply find the literature that supports your theory or assertions, and ignore the ones that don’t! That way, you can say whatever it was that was rolling around in your head anyway, but NOW with a lot of science-y looking figures! YAY!

LikeLike

There’s nothing cogent in this response lol

LikeLike

Really – no reply? Nothing says “science” like refusing to engage with peers…

LikeLike

How can anyone take what you said seriously, when you didn’t even link a single study contradicting this article? Now it just sounds like you’re venting your frustration caused by cognitive dissonance.

LikeLike

Pingback: How Racist are White Americans? | Ideas and Data

Pingback: Justice for George Floyd – Zeke Jeffrey

The number of Grammatical errors in this was amazing. Also, you misused statistics.

LikeLike

Great article. The current state of intellectual discussion is appalling, the amount of fallacies and arguments from anecdote out there is unbelievable. I’d like to see more people tackle this issue and gross lapse in critical thinking – which is unfortunately not taught in many schools.

LikeLike