This post will argue that, on net, white Americans do not act in a way that could properly be described as racist, though they might have beliefs and feelings which some would describe as racist, but not to the degree that other racial groups do.

Importantly, this post is not about institutional racism. I have separate posts dedicated to supposed examples of institutional racism such as call-back studies, racial bias in lending, racial bias in police shootings, arrests, pull overs, and criminal sentencing, racial bias in education funding, etc.

What this post is about is white Americans as a group. It isn’t about what specific subsets of whites, such as police or employers, may or may not be doing. These subsets of people are of course counted in group averages, but even if they, or any other subset of whites, exhibit a pro-white bias the racial bias of white Americans as a whole can still be zero if there is another subset of whites who exhibit an equally strong anti-white bias.

Establishing that white people do not exhibit racist behaviors is important for two reasons. First, it is important because white people have unfairly come to be associated with racism in the public consciousness.

Secondly, it is important because it establishes a key empirical prior. If whites on average do not behave in a racially biased way, then, on average, any random subset of whites will also not behave in a racist way. Given this, it is proper to assume that any given subgroup of whites (for instance employers, police, and judges) do not behave in a racist way until evidence to the contrary is given.

This is a rejection of the view that we should be agnostic about the racism of whites until context specific evidence is presented, and this, in conjunction with my previous post about the epistemic invalidity of lived experience, gives us reason to positively reject claims of society wide racism that are merely based on personal experience rather than merely saying that they are unproven. In other words, we should assume that any given group of whites do not act in a racist way, and the burden of proof is on anyone claiming otherwise, and personal experience does not meet this burden of proof.

Because this is an empirically driven prior, it need not apply equally to all groups. In fact, in this post we will see evidence that black Americans do, on net, behave in a racially biased way. Given this, it is proper to assume that any subset of African Americans also behave in a racially biased way and the burden of proof is on those claiming that this is untrue of any particular groups of African Americans.

Discriminatory Behavior

Turning to the empirical evidence, there are experimental tests of discrimination. In this research, people are asked a variety of questions such as whether they would vote for a given politician, whether a described person’s problems are primary their own fault, or whether a described individual deserves help. Prior to being asked these questions, people are assigned to one of two groups. For each question, the described individual will be black in one group and white in the other. No other differences will exist between the two people.

Zigerell (2018) meta-analyzed 17 such studies and found that white people exhibited a statistically insignificant tendency to favor black people while black people exhibited a pro black bias that was larger and statistically significant.

Similarly, Mitchell et al. (2005) analyzed data from 34 studies in which people acted as jurors and voted on whether a given defendant was guilty. It was found that whites exhibit nearly no racial bias in such decisions while black people exhibit an in-group bias that is 15 times larger than the minuscule bias seen among whites.

With respect to deciding sentence length, racial bias among white people was still practically insignificant, while the bias among black people was 7.6 times greater.

Assuming normal distributions, these values imply that white people favor harsher sentence lengths for the average black criminal than they do for 54% of white criminals while black people favor harsher sentences for the average white criminal than they do 77% of black criminals. (50% would imply absolutely no bias).

Devine and Caughlin (2014) conducted a similar meta-analysis finding that white jurors had no bias against black defendants but did have a slight bias against Hispanic defendants. Black jurors, once again, exhibited a pro-black or anti-white bias.

More recently, Burge and Johnson (2018) conducted a study finding that black Americans favor harsher punishments for white on black crime than they do for black on white crime.

The next meta-analysis worth mentioning only examined racial bias among white people so it doesn’t allow for a comparison of bias by race. Saucier et al. (2005) meta-analyzed 48 studies comparing how much help white people offered to strangers and how that varied depending on whether the stranger was white or black. On average, there was no difference, suggesting, once again, that white people act in a pretty egalitarian manner.

There were, however, ways of cutting the data that caused differences to emerge. To produce this result, studies were separated based on how hard it was to help the stranger and how much they needed the help. When helping people was easy and no one was in dire need of help, white people exhibited a slight bias in favor of black people. When helping people was easy and the people in question were in great need of help, there was a bias in favor of white people. When helping people was hard, there was no difference in white people’s propensity to help others based on race.

In order to say what these results imply about behavior in the real world, we have to consider the frequency of each sort of incident. It seems obvious to me that we often see people who we could easily help in a way that would slightly benefit them. It seems much rarer to find ourselves in a situation where we are considering helping someone who we could help greatly with little effort on our part. Given this, I suspect that incidents in which white people exhibit a pro-black bias are far more common in the real world than incidents where white people exhibit a pro white bias. In any case, it also seems obvious that these already weak effects will wash out so that the average bias is essentially zero.

Thoughts and Behavior

Another method of measuring racism is to look at how people react when they are assigned to interact with members of another race in an experimental setting. In these studies, people are assigned into pairs and told either to complete some task or have an unstructured social interaction with their assigned partner. Following this, participants report how they felt about their partner, as well as their general emotional states, and in some studies non-verbal body language was rated by observers and, if people were assigned a task, their performance on that task was recorded.

These studies differ from the ones we’ve looked at so far in that they measure both behavior and how people feel. The research examined so far has all been about behavior and it is possible for people to act in an egalitarian way even if their feelings exhibit a racial bias.

Toosi et al. (2012) meta-analyzed data from 108 samples taken from this literature and found that there was a weak, but statistically significant, tendency for each outcome to be more favorable among same race pairs of people.

Minorities and white people did not significantly differ in their degree of in group bias when this was measured in terms of their objective performance on a task, or how they said they felt about their partners. However, among minorities their reported general emotional state and body language did not differ according to the race of their partner while this was not true of white people.

Importantly, these effects have been declining with time. Studies done many decades ago found practically significant effects but research done within the last 15 years finds trivial effects on all outcomes.

It’s also worth noting that people’s explicit attitudes towards their partners, and their body language, used to exhibit the strongest effect sizes. Today, people’s general emotional state and group performance are the strongest effects. This is consistent with people learning to hide their discomfort with racial diversity, but it should be emphasized that even the strongest of these effects is quite weak. For all measures, around 1% or less of the variation in outcomes is explained by the racial homogeneity of the pair of people involved.

Ethnic Identity

While not the same as racism, the degree to which people say they identify with their ethnic group and consider their ethnic identity to be important is clearly a related construct. The data in this area consistently shows that white people exhibit less ethnic and racial identity than do non-whites.

For instance, when asked how important it is that people of their ethnic group marry other members of their ethnic group, white Americans of most ancestries are considerably less likely than non-white Americans to say that intermarriage is important. This is especially true if you don’t count Jewish people when calculating the white average, as Jews are a mixed ethnic group and happen to be even more likely than completely non-white ethnic groups to say that intermarriage if important.

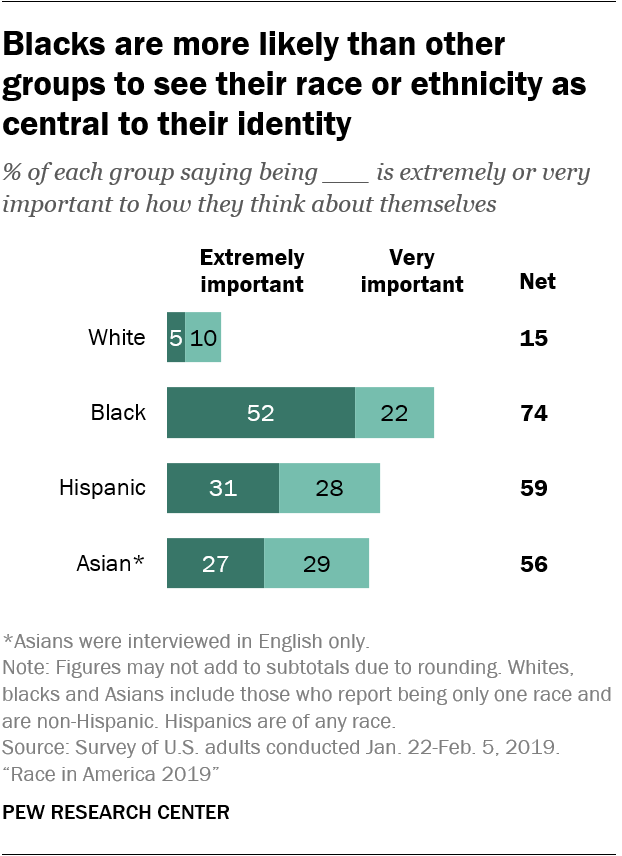

We see similar results from a recent Pew poll which found that most minorities consider their ethnicity to be an important part of their identity while only 15% of whites do.

This is also consistent with various studies that employ more complex measures of ethnic identity. For instance:

Thus, most white people do not consider their ethnicity to be an important feature of who they are, while minorities, especially African Americans, are considerably more likely to do so.

Implicit Bias

So far, we’ve only looked at measures of racism which allow people to lie. Now, these studies are not conducted in a way that lets participants know that they are trying to measure racial bias, so there is no obvious reason to think that they would lie, but it is still a possibility that people lie about how they feel and act in a non-racist way despite secretly having lots of racist feelings. To get around this difficulty, some people look to the implicit association test.

In these tests, people see pairs of words or images and press a key to assign them as being “good” or “bad”. This good or bad decision is not entirely free. Participants are told to categorize certain items as good or bad. Sometimes, when people are told to put words or images associated with black people into the “good” category they take something like half a second longer to press the “good” button than when white people are paired with good items. Sometimes the opposite pattern occurs so that people take half a second longer to press the “negative” button for white faces than they do for black faces. To the degree that this occurs, people are said to have an implicit, and possibly unconscious, bias against black people.

On the basis of this research, Chris Mooney at the Washington Post claims that “Most white Americans demonstrate bias against blacks, even if they’re not aware of or able to control it. ” Then this map is presented showing racial bias among whites by state:

It’s worth noting that implicit bias against black people is declining with time. Roughly 17% of the total bias was eliminated just between the years 2007 and 2016.

Charlesworth and Banaji (2019)

It’s also worth noting that the average degree of bias found is “weak” according to commonly used guidelines for interpreting effect sizes.

It’s also important to mention that there is controversy concerning whether the IAT actually measure anything. Generally, researchers like metrics that exhibit good reliability, meaning that the same person taking the test multiple times will get roughly the same result, and good validity, meaning that it correlates well with the things we think that it should correlate with if it is measuring the thing we are trying to measure.

The IAT has a test-retest reliability in the .4 to .5 range which is lower than what is normally considered acceptable for a psychological test (Goldhill, 2017). This implies that the same person taking the IAT twice would often get significantly different results.

Defenders of the IAT have pointed out that it’s internal reliability is higher than its test-retest reliability. So, for instance, if you arbitrarily divide the IAT test in half and score each half independently, the correlation between the two halves taken by the same person will be in the .6 – .7 range which is at the lower limits of acceptability in psychometrics (Jost, 2018). The fact that the split-test reliability of the IAT is significantly greater than the test-retest reliability of the IAT implies that whatever the IAT measures changes a good deal within individuals over the course of weeks or months.

These reliability estimates are low, but they are inconsistent with the view that the IAT doesn’t measure anything. If that were true, its reliability would be zero, and its not.

With respect to the validity of the IAT, there is a good deal of variation depending on what we are trying to predict. The IAT does not correlate at all with experimental measures of racial bias in behavior, so it has no validity in this area. So, whatever the IAT is measuring, it has nothing to do with whether people will treat a black person differently than a white person assuming no other differences between the people.

When IAT scores do predict a relevant criterion, the correlation is generally less than .20, meaning that IAT scores predict less than 4% of the variance in these outcomes.

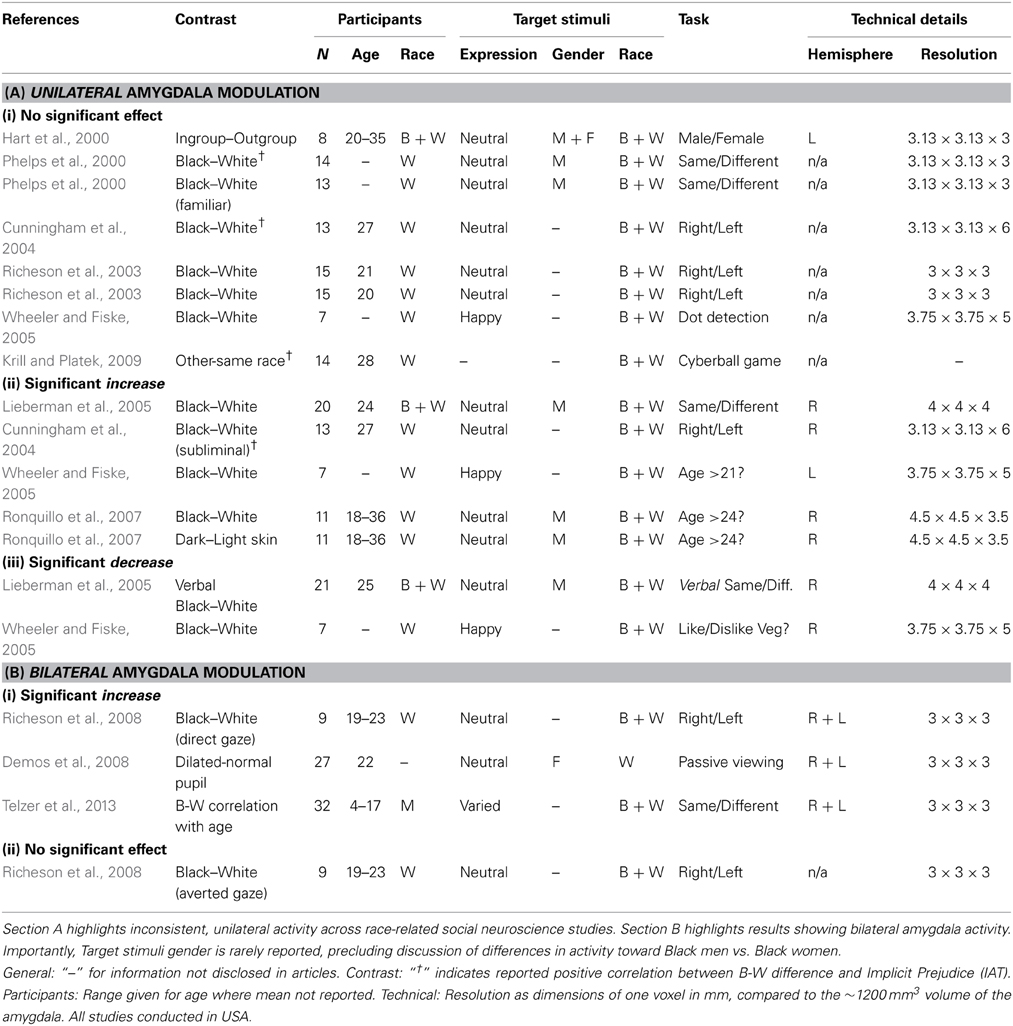

The major exception here is “brain activity”. The IAT is a reasonably good predictor of certain sorts of brain activity, normally amygdala response. Amygdala response is relevant because there is a separate literature linking differences in how people’s amygdala’s respond to people based on race, and racism.

We might be tempted to interpret this as the IAT predicting the one variable that people really can’t hide, their neural responses. However, this neuro-imaging literature consists of many studies with tiny samples, normally less than 20 people, and most of the research has failed to find a link between amygdala response and racial bias.

Given this, we have good reason to think that the IAT does not measure a person’s propensity to engage in racially biased behavior, and we don’t have any good reason to think that the IAT is even a good measure of racial bias that is not acted upon. There is some reason to think that it has some predictive power in this area, but that predictive power is very weak. Overall, it is not convincing evidence of significant racial bias among white Americans.

Explicit Preferences

We can also measure racial bias by directly asking people how much they like various ethnic groups and compare this to how much they say they like their own group. The obvious flaw in this research is that participants are aware of the fact that they are being asked about race and so have an incentive to lie.

Meta-analysis of this sort of research finds that white Americans have a weak and declining preference for their own group equal to roughly .20 SD. The trend in this preference is such that it is expected to reach zero sometime between 2 an 22 years from now.

Charlesworth and Banaji (2019)

Comparing this sort of preference by race, we see that non-whites exhibit a greater in-group bias than whites do, and that white liberals actually prefer other groups to their own ethnic group.

We see something similar if we look at which race white and black Americans say they feel the closest to. The majority of white respondents say that they feel equally close to black and white people.

Black Americans, by contrast, are more likely to say that they feel closer to fellow black people, though the gap here is not very large.

It’s worth noting that both groups have changed their answers significantly since the 1990s when both groups exhibited a much stronger in-group preference. It is also worth noting that both groups are more likely to say they feel closer to their own race than the other race, and so if we averaged these scores out they would indicate some degree of net in-group bias in each group, and this in-group bias would be stronger among black people than among white people.

We see a similar trend when looking at polling that asks white people how they would feel about living in a majority black neighborhood. In the early 1990s, white Americans were most likely to say that they would oppose living in such a neighborhood. Today, most white Americans say that they would neither favor or oppose it and while a subset of whites still oppose living in a majority black area there are roughly as many whites who say they would actively favor such a situation bringing the average in-group bias down to something slightly positive but near zero.

Turning to inter-racial marriage, we see that most white people opposed interracial marriage until the mid 1990s and that today less than 20% of white people maintain this attitude. This particular measure is not constructed in a way that would allow the expression of an anti-white bias, and so its average necessarily indicates pro-white bias so long as there is at least one white person who opposes inter-racial marriage. Thus, this measure cannot be used to gauge the net degree of racism among whites.

It is interesting that white people possess a small but real in-group preference but act in an egalitarian manner. Though that preference is declining, this suggests that, for the time being, white people are acting in a way that is not in line with their racial preferences.

It is also interesting that white people’s in-group preference declined so much between 1990 and 2005. In popular culture, it is sometimes suggested that the 1960s and 1970s where when white america changed its mind about things like interracial marriage or living near black people, but this is clearly wrong.

On Stereotypes

A final way we might measure racism is by looking at the degree to which white people endorse stereotypes about black people. However, this approach is problematic because literature reviews on stereotype accuracy find that stereotypes are generally accurate and, in the case of commonly shared stereotypes about race, are rated as highly empirically accurate more than 95% of the time (Jussim et al., 2015).

For instance, most white Americans endorse the stereotype that black people are poorer than white people, and this is simply factually true. It seems problematic to me to count this as a measure of racial bias when it is the conclusion that any unbiased observer would come to.

In any case, the endorsement of racial stereotypes is declining with time, but more than 20% of whites still think that black people are less intelligent than white people and more than 30% of white people think that black people don’t work as hard as white people do.

Before interpreting these results, we should consider four facts about race and intelligence.

First, meta-analyses of data on millions of participants show that black people score lower than white people do on intelligence tests.

Second, most experts agree that such tests are not racially biased because they pass formal statistical tests for test bias.

Third, Black Americans also score lower than white Americans on measures of emotional intelligence. In fact, on objective measures of emotional intelligence the black-white gap is roughly as large as the black-white gap in IQ. Black people do score higher on self report measures of emotional intelligence, but the self report data is clearly “wrong” in this case.

Fourth, black Americans score lower than white Americans on measures of practical intelligence having to do with how to deal with real world situations.

Given this, it seems obvious that someone could conclude that black people are, on average, less intelligent than white people without harboring any sort of race based hatred or bias. Even if this conclusion is ultimately wrong, you would not need to be a racist to think that it is right.

We should also consider three facts about hard work. First, black Americans are less likely than white Americans to have a job.

Second, while at work black Americans spend more time than white Americans not working.

Third, as children black Americans spend less time than white Americans doing homework.

These stereotypes concerning intelligence and hard work are like the stereotype that black people are poorer than white people. They are what someone would think if they just looked at the data. The fact that most white people today do not believe these stereotypes speaks, I think, to them having a worldview that is biased in favor of non-white people.

In any case, the evidence reviewed earlier shows that white people do not let these stereotypes influence how they treat individuals, and that strikes me as a better measure of “racism” than factual beliefs about the world.

Conclusion

To sum up, behaviorally, white people exhibit no racial bias while black people do. White Americans do have an in-group preference but it is weaker than the in-group preference seen in other groups and is quickly fading with time. White people have a weaker sense of ethnic identity than do non-whites. Some people point to IAT data, or data on people’s beliefs in stereotypes, as evidence that white people are racist, but neither of these lines of evidence actually justify that conclusion.

Our prior should be that white people are less racially biased than non-white people, and, in the case of behavior, that white people are not biased at all. People who accuse groups of white people of racism must therefore provide evidence demonstrating that this is true and if the evidence offered does not sufficiently justify the charge of racism then said charge should be assumed to be false.

Pingback: Racial Bias in Police Stops and Searches | Ideas and Data

Interesting stuff as usual, Sean. Keep it up!

LikeLike

Sean, you labelled the percentage of English people who are say intermarriage is important on your graph, it should be 28.4%, not 18.4%

LikeLike

Pingback: Race Differences in Aggression – g-loaded

Pingback: Children of the Grave: Ethnic Identity and Psychological Well-Being – Race & Conflicts

Pingback: Race Differences in Aggression – Race & Conflicts