The purpose of this post is to document the basic facts concerning the relationship between IQ scores and individual success in the economy and in education.

Simple Correlations

The first thing to establish is the bi-variate relationship between IQ and these outcomes. Strenze (2015) gives estimates of .20 to .27 for the correlation between income and IQ. This correlation is modest in size, but it is greater than the correlation between income and a person’s race, gender, and personality, as well as the income of their parents.

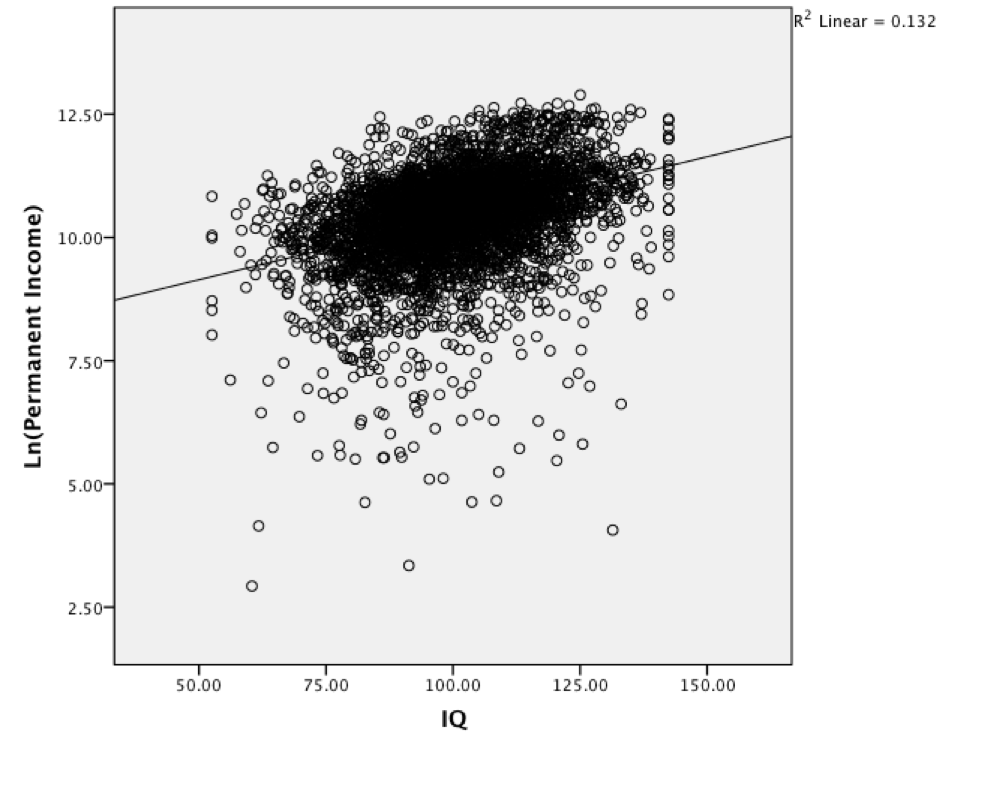

Measuring income can be a tricky since temporary events like unemployment or selling a house can cause a person’s income to significantly differ from what it usually is. If income is averaged over several years, the correlation with IQ raises to .36 meaning that IQ explains 13 percent of variation in income and that a one point increase in IQ predicts a 2.5% increase in income (Dalliard, 2016).

The relationship between cognitive ability and income has been established in many countries. Interestingly, Strenze (2015) finds that strength of the relationship between cognitive ability and income is negatively related to a nation’s wealth.

IQ also has a strong relationship with direct measures of job performance. Meta-analyses show that IQ is a better predictor of job performance than are variables like work sample tests, reference checks, years of experience, and age.

(Roth et al., 2005; Schmidt and Hunter, 1998)

Structured interviews, in which the interview is planned in detail and a script is followed by the interviewer, are roughly as predictive of job performance as are IQ tests. This is an impressive result since structured interviews are designed to get all the information they can from someone that is relevant to the job while IQ tests don’t directly involve any aspect of the job in question.

Schmidt and Hunter (2004) reviewed the relationship between IQ and job performance and highlighted several interesting details. First, there is a great deal of variation in IQ within occupations. The range of IQ within each occupation suggest that a minimum IQ is required to engage in some jobs, but there is no maximum IQ for an occupation. In other words, you find some exceptionally smart people in every line of work, but in cognitively demanding jobs you won’t find any people with quite low IQ scores.

When jobs are categorized according to their cognitive complexity we see that the validity of IQ is only .23 in the simplest of jobs and as high as .58 in the most complex jobs.

The validity coefficient among computer programmers is even higher coming in at .73 suggesting that the majority of variation in income among programmers can be predicted on the basis of IQ.

The validity of IQ also increases with time, such that it has a validity coefficient of .59 among people who have 12 or more years of experience.

Another important predictor of income is conscientiousness, a personality factor that measures traits like self discipline and organizational ability. Hunter and Schmidt conducted an analysis using an index of career success created out of occupational status and income. When both IQ and conscientiousness were entered into the same model, IQ was found to correlate at .43 with career success compared to a correlation of .27 for conscientiousness. The other traits contained within the Big 5 model of personality were not significant predictors of career success.

The same paper finds that IQ correlates with job performance primary by impacting job knowledge. But IQ has some validity independent of job knowledge, suggesting that most jobs require the everyday use of the cognitive skills measured by IQ tests.

(GMA is General Mental Ability).

Bertua et al. (2005) report similar findings in their review of the literature from the UK, reporting that IQ correlates at .42 with job performance, and .49 with training success. They also replicated the finding that the validity of IQ varies by occupation with IQ correlating at at .32 with job performance among clerical workers and .69 with job performance among managers.

Turning to education, meta-analytic reviews suggest that IQ’s correlation with grades increases with age and that it explains roughly half of the variation in GPA by the time people are in college.

| Citation | Age | K | N | R |

| Roth et al. (2015) | Elementary School | 71 | 18584 | 0.45 |

| Roth et al. (2015) | Middle School | 75 | 49771 | 0.54 |

| Roth et al. (2015) | High School | 71 | 15427 | 0.58 |

| Postlethwaite (2011) | High School | 32 | 13290 | 0.65 |

| Postlethwaite (2011) | College | 78 | 16449 | 0.72 |

Of course, academic performance can be measured in a variety of ways and intelligence is more correlated with some than others. With respect to standardized tests, the correlations with IQ are so large as to imply that these tests essentially are IQ tests. This is true of the SAT, the ACT, and Britain’s GCSEs.

| Citation | Test | Correlation | N |

| Brodnick and Ree (1995) | SAT – V | 0.8 | 339 |

| Brodnick and Ree (1995) | SAT – M | 0.7 | 339 |

| Brodnick and Ree (1995) | ACT | 0.87 | 339 |

| Frey and Detterman (2004) | SAT | 0.86 | 917 |

| Frey and Detterman (2004) | SAT | 0.72 | 104 |

| Beaujean et al. (2006) | SAT | 0.58 | 97 |

| Deary et al. (2007) | GCSE | 0.81 | 70000 |

Parental SES as a Confound

A large amount of research shows that IQ correlates with these outcomes even when holding parental socio-economic status constant. The chart below shows the association between IQ and various outcomes after controlling for some measure of parental SES.

| Citation | Outcome | Standardized Beta | N |

| O’Connel (2018) | Math Scores | 0.6 | 7147 |

| O’Connel (2018) | Reading Scores | 0.51 | 7147 |

| Colom etl al. (2007) | Scholastic Achievement | 0.69 | 372 |

| Colom etl al. (2007) | Scholastic Achievement | 0.6 | 100 |

| Colom etl al. (2007) | Scholastic Achievement | 0.64 | 169 |

| Thienpoint et al. (2004) | Social Class | 0.41 | x |

| Kemp (1955) | Educational Achievement | 0.47 | x |

| Murray (1998) | Income | 0.31 | 1579 |

| Saunders (1997) | Occupational Status | 0.25 | 6000 |

Notably, these associations are similar to what the bi-variate correlations are, implying that parental SES doesn’t contribute much to these relationships.

A few more studies are worth mentioning. First, in Brodnick and Ree (1995)‘s model IQ is extremely predictive of standardized test performance and adding parental SES to the model did not improve it’s accuracy at all (N=339).

Second, in a sample of 1,454 veterans, Grilches et al. (1972) found that IQ (AFQT) predicted income after controlling for race, education, region, as well as paternal education and occupation. These effects aren’t standardized, and so were not included in the above table.

(This table is also noteworthy because it suggests that racial differences in income used to persist even after holding IQ constant.)

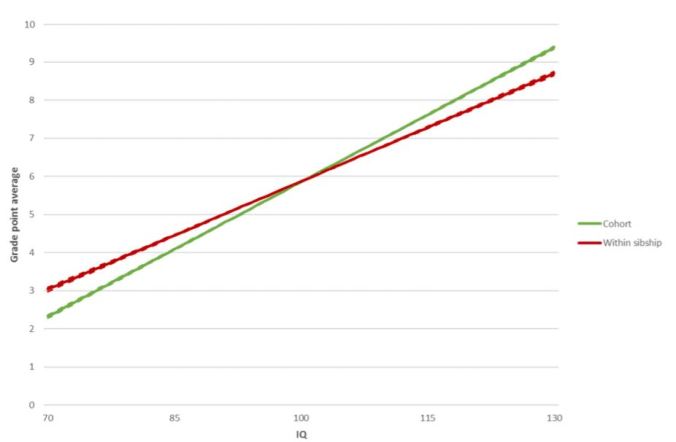

Third, along with providing a regression included in the above table, Murray, (1998) showed that IQ predicts life outcomes within families. That is, within a given pair of siblings the sibling with the higher IQ typically ends up better educated, richer, and working a higher status occupation, than does their less intelligent sibling. The results of this sibling analysis are remarkably similar to regular regression results despite employing a much stronger control for the home environment.

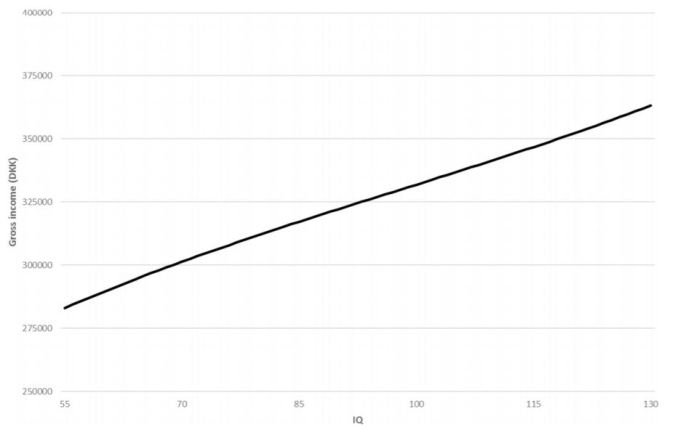

Hegelund et al. (2019) show similar results using a sample of 364,193 Danish men.

They find a similar result when looking at IQ’s correlation with welfare use.

It is note worthy that the relationship between IQ and life outcomes doesn’t attenuate much if we control for every aspect of the home environment rather than crude measures like parental income and education. This suggests that any home environmental variables with confound IQ’s relation with life outcomes, and any home environmental variables which have a causal impact on IQ, are well captured by crude measures of parental SES.

Finally, turning to longitudinal research where IQ is measured many years before the relevant life outcome, Strenze’s meta-analysis shows that parental socio-economic status is a weaker predictor than IQ is for education, income, and occupational status.

Thus, there are multiple lines of evidence showing that IQ’s relationship with life outcomes is not explained by parental socio-economic status.

Relationships that are Linear

Sometimes, it’s wondered whether the relationship between IQ and these outcomes persists beyond a certain threshold. Often, these relationships are consistently linear. For instance, Hegelund et al. (2018) analyzed data on over one million participants from Denmark and produced the following graph:

The relationship between IQ and income/wealth is also pretty linear in the United States.

Similarly, Coward and Sackett (1990) analyzed data from 174 studies on the relationship between IQ and job performance. A non-linear trend fit the relation better than a purely linear one only between 5 and 6 percent of the time, roughly what one would expect on the basis of chance alone.

Arneson et al. (2011) analyzed four large data sets on the relationship between IQ and education or military training outcomes and found in all four cases that the relationship was best described with a linear model.

That being said, the “Project Talent” relationship is obvious less linear than the others despite the fact that a non-linear relationship didn’t significantly improve the accuracy of the model.

Relatedly, Frey and Detterman (2004) found IQ to correlate non-linearly with SAT scores (N = 917).

However, this result is not typical. Coyle (2015) finds that IQ’s relationship to GPA, ACT, and SAT, scores is not better described by a non-linear model in a much larger sample.

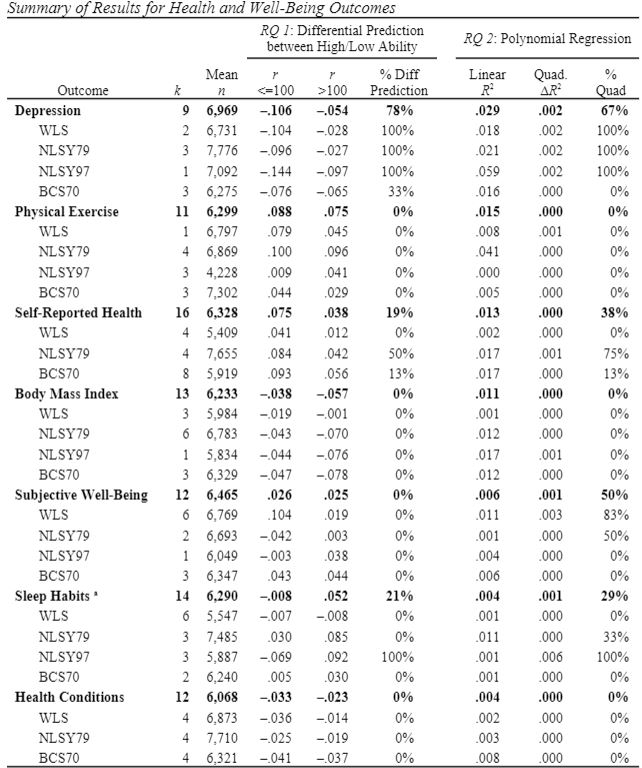

Brown et al. (2020) analyzed data from multiple American data sets contrasting the validity of linear and polynomial regressions for numerous life outcomes, as well as comparing the correlation between IQ and these outcomes for people with below and above average IQs. As can be seen, these results suggest little could be gained by using non-linear models for these outcomes.

Relationships that are not Linear

That being said, some economic outcomes are clearly not linearly associated with IQ. For instance, Hegelund et al. (2018) find that unemployment, welfare use, NEET status, and educational attainment, are only associated with IQ up to a certain point on the IQ distribution in Denmark.

Sometimes, it’s found that IQ increases in predictive validity as you move up the IQ distribution. For instance, this seems to be true of several outcomes related to science as well as being rich:

Park et al. (2008) find that this is true of science outcomes even when only looking at those in the top 1% of the IQ distribution.

Thus, the linearity of IQ’s relationship with outcomes varies, but the outcomes people are normally most concerned with, job performance, GPA, and income, exhibit pretty linear relationships. When IQ’s relationship with an outcome is non-linear, this is usually because the outcome is not a continuous measure and therefore cannot measure the effects of variation in IQ past (or under) a certain threshold.

Generational Changes in Predictive Validity

Sometimes, it is suggested that IQ’s relationship with income is increasing with time leading to more “cognitive stratification” while IQ’s relationship with educational attainment is falling. Strenze et al (2007) provides some of the best evidence on this question, finding that IQ’s relationship with education hasn’t changed much over time while it’s relationship with income was falling until the 1970s and has since returned to its early 20th century level.

On the other hand, Roth et al. (2015) IQ – GPA Prior to 1983, the correlation was .68 (K = 100, N = 35,046), and after 1983 the correlation was .47 (K = 140, N = 70,139). So evidence on education is somewhat mixed, but this may be an arbitrary result of the bins that Roth et al happened to select.

It has also been shown that the mean vocabulary score gap between college and non-college educated Americans has been falling for decades.

This was an inevitable result of increasing the proportion of the population attending college.

Conclusion

To conclude, IQ has an important relationship with educational and economic outcomes that cannot be explained by confounds from the home environment. In general, IQ explains more variation in outcomes than do other predictors, but it explains a good deal less than half of the total variation in the outcome of interest (e.g. income, GPA, etc.) unless we are talking about performance in highly complex jobs, or scores on standardized tests that are themselves essentially IQ tests. For the most part, these relationships are consistently linear. Non-linear relationships are typically found when using a non-continuous dependent variable. Finally, these results are persisting into the present day.

Sean, you ought to point out the spuriousness of the Frey and Detterman (2004) paper since it’s one of the main pieces of evidence Taleb used in his post on IQ. Look at the graph’s y axis – there’s not a single person in the study with an IQ above 130. The reason why the relationship between IQ and SAT dissipated on the right-side of the plot is because of this artificial ceiling. The IQ test used in the paper didn’t allow for scores above 130, and this can be seen on the graph. It shatters Taleb’s arguments about IQ not being important in the upper range for academic success.

I want you or Ryan to point this out eventually, it hasn’t been addressed and seems to have gone unnoticed by most people who read his article.

LikeLike

Pingback: RANDOM REVOLUTIONS | Veiko Klemmer

Pingback: INTELLIGENCE OR DEATH | Veiko Klemmer