Racial differences in the ability to acquire a loan are sometimes pointed to as evidence of white privilege or anti-black bias. These differences are said to lead to racial disparities in home ownership rates which in turn have a variety of long-term economic and social consequences.

Data from Pew shows that black people are indeed more likely to be denied for a mortgage loan. However, even among blacks the rate of denial is only 27%.

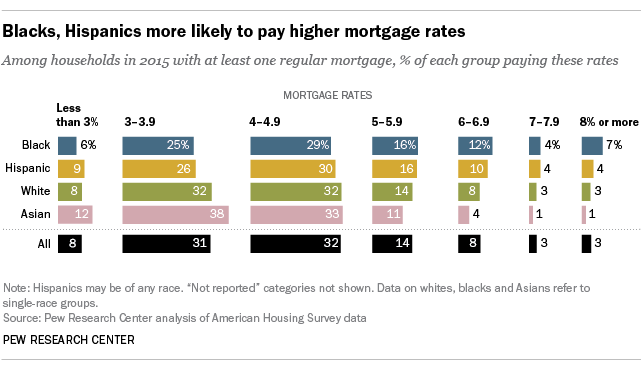

Turning the interest rates, it is true that Black people are more than twice as likely as whites to get a mortgage interest rate of 8% of more. But this is very rare even among black mortgage holders. The average interest rate seems to be similar among whites, Hispanics, and blacks, though possibly significantly lower for asians.

The Standard Left Wing Case

To show that these disparities are due to racial bias, leftists try to show that black people have a harder time getting loans even after controlling for economically relevant variables. For instance, some have pointed out that Whites are more likely than Blacks to get loans approved when comparing people of equal incomes.

But it would be fallacious to infer from this that racial bias was at work since Blacks and Whites with equal incomes do not have the same spending behavior. For instance, Borgo (2013) looked at data on 25,820 American households and found that Black homes had lower saving rates than White homes even after controlling for differences in income, age, family size, education, and marital status. Thus, it makes sense for banks to prefer White customers over Black ones even if they have the same incomes.

Such differences in behavior explain why Blacks and Whites with equal incomes do not have the same credit scores. As reported by The Washington Post:

“The study found that whites earning less than $25,000 had better credit records as a group than African Americans earning between $65,000 and $75,000. Overall, 48 percent of blacks and 27 percent of whites had bad credit ratings, as defined by Freddie Mac in this study.” – Loose, The Washington Post

That being said, some studies find that racial differences in loan acceptance persist even after adjusting for credit score differences. This is true, but it is also true that the credit scoring system doesn’t work equally well for Blacks and Whites. Consider the follwing from a report given to congress by the federal reserve on how well loan performance is predicted by credit scores:

“Consistently, across all three credit scores and all five performance measures, blacks… show consistently higher incidences of bad performance than would be predicted by the credit scores.”

In other words, if you give out a loan to a Black and a loan to a White with equal credit scores, you are more likely to get your money back from the White.

So, the normal attempts to control racial differences in loan risk are insufficient and cannot be taken as providing good evidence for the existence of racial bias.

Evidence Against Racial Bias

That being said, there are at least four lines of evidence which suggest that racial differences in loan acceptance, and interest rates, are due to race being accurately used as a proxy for investment risk and not due to racial animus.

First, this is suggested by the pattern of racial differences in approval rates by credit score. The previously noted report explains that black people being more risky than white people to give loans to after holding credit scores constant is mostly true of those with low credit scores. Among those with high credit scores, there isn’t must of a difference. Now, a study by the Chicago federal reserve found no racial bias in loan approval rates among those with a good credit score but a significant bias in favor of whites among those with a bad credit score. Similarly, Ross et al. (2004) find that black borrowers have a tougher time getting loans but this is only true among those who don’t have mortgage insurance. Thus, lenders are acting exactly as we would expect them to if they were accurately using race as a proxy for investment risk.

The second line of evidence deals with default rates by race. Like many studies, Berkovec et al. (1994) find that loans taken out by black people are more likely to end in default. This remains true after controlling for the size and type of loan as well as characteristics of the borrower such as their age, income, and liquid assets value. If you think black people are discriminated against in the loan market you might expect that black people must meet higher standards, and so ensure a lower risk of default, than white people in order to get loans. These results show that this is not true and so this is evidence against racial bias.

Some may claim that high default rates among black borrowers are to be expected because they are charged far greatest interest rates than whites are. This explanation is not compelling though given the size of the unexplained gaps in interest rates between races which remain after controlling for obvious confounds. For instance, Cheng et al. (2014) analyzed data from the U.S. Survey of Consumer Finances from the years 2001, 2004, and 2006 and found that controlling for measures of consumer behavior and debt risk reduced the black-white average interest rate gap to .29%. This remaining gap is small and may itself be explained by variables correlated with race which Cheng et al. did not measure. In any case, it seems unlikely that an interest rate gap of this size could explain racial gaps in default rates.

Moving on, in my view, the strongest evidence against racial bias in lending comes from Bhutta and Hizmo (2019). They analyzed a data set consisting of all FHA-insured mortgages that originated in 2014 and 2015. After controlling for lender effects, credit score, and income, they found a black-white interest gap of .03% and a Hispanic-white gap of .015%. This result is similar to what we’ve already seen, but, unlike most research in this area, Bhutta and Hizmo also included data on discount points and this revealed a racial difference in favor of non-whites. Combining this data into a single model, they found no racial bias in borrower’s expected pay schedule’s. Even more importantly, it is shown that the expected revenue generated by a loan does not significantly differ by the race of the borrower.

This evidence is very hard to reconcile with racial bias. The fact that, once other differences are held constant, races experience the same expected pay schedules directly suggests that no bias exists. The fact that the expected revenue of loans does not differ by race strongly suggests that the differences in the terms of loans given to blacks and whites reflect lenders accurately forecasting the terms which will maximize profit within each race of borrowers. It is hard to see how this result could come about if people were acting on the basis of racial animus rather than economic rationality.

Finally, more evidence that racism is not the cause of differences in loan approval rates comes from a study of several thousand banks which found that Black-owned banks discriminated far more harshly against Blacks than did White-owned banks.

Specifically, at a White owned bank a Black person was found to have a 78% higher chance of rejection for a loan compared to a White person. At a Black-owned bank, this figure rose to 179%, an increase of 101%.

Thus, racial differences in the riskiness of loans seem to account for why Blacks have a harder time getting loans than White people do, and why their interest rates tend to be slightly higher.

On Redlining

A narrative related to racial bias in lending concerns the practice of redlining. Essentially, the idea is that in the 1930s the US government created maps demarcating certain neighborhoods as high risk for investment. One of the variables they utilized when estimating an area’s degree of risk was that area’s racial composition. Lenders then became less likely to give out loans to people in these communities and, through public housing and zoning laws, black people were moved into these same communities making them even blacker than they initially were. Thus, black people are said to be at a disadvantage in the loan markets because of the neighborhoods they live in.

Importantly, this bias only impacts race indirectly. The discrimination is directly on neighborhoods and so should apply equally to people of all races who live in these majority black areas.

So, that’s the story. It’s been tested many times and shown fairly consistently to be false. This falsification consists of studies showing that the probability of people getting a loan does not relate to the racial composition of their neighborhood once economically relevant con-founders are controlled for.

For instance, Ahlbrant (1977) found that the race had no significant independent effect on loaning in a data-set from Pittsburgh. Hutchinson et al. (1977) found the same thing in Toledo, Ohio. (However, the loans given in black areas were disproportionately backed by the government.). Similarly, Dingemans (1979) analyzed data from Sacemento, CA, and found that “Once the effects of socioeconomic status variations are accounted for, measures of ethnicity or age of the housing stock contribute little explanation”. (The regression output was not shown or explained in detail verbally).

Avery and Buynak (1981) analyzed data from Cleveland, Ohio, and found similar results. Blacker areas received fewer loans from private sources, but received more loans from mortgage firms, the majority of which were government backed. The total amount of loans given in an area was generally unrelated to its racial composition. The exception here is areas which rapidly changed in racial composition. In such areas roughly 9% fewer loans were given. But areas that were stably black or stably white did not significantly differ in loan rates once economically relevant variables were held constant.

Finally, Tootell (1996) analyzed data from Boston and found that the racial composition of an area was unrelated to the proportion of loan applications that were rejected (Bradbury et al. 1989 fond a significant effect for race in Boston but their regressions omit more variables).

The idea that redlining increased racial inequality also seems unlikely in light of the fact that the black-white home ownership gap today is similar to what it was in the 1920s before redlining began.

Conclusion

Thus, the idea that black neighborhoods are racially discriminated against in a way that prevents their inhabitants from getting loans, and that this is tied to redlining from the 1930s which increased racial inequality, seems to be false. So does the idea that black individuals are unfairly discriminated against. Instead, lenders seem to be accurately using race at the individual and neighborhood level as proxies for investment risk and that is not racist.

Pingback: How Racist are White Americans? | Ideas and Data

What about this? https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/wp2017-12-pdf.pdf

LikeLike

What is that article about?

LikeLike

Lol, what does that have to do with this?? “Our results provide strongly suggestive evidence that the HOLC maps had a causal and persistent effect on the development of neighborhoods through credit access.”

LikeLike

Pingback: Response to Vaush: The Ultimate Research Collection – BioRealismBRx

Pingback: Day Bidet #8 – Brave Ole World

Pingback: Vaush Response [NOT FINISHED] | Vinum Daemoniorum

Pingback: IQ and Interest Rates | Anglo Reaction