In this post, I want to document the relationship between Protestantism and the rise in Western civilization that occurred via the Industrial revolution, the Enlightenment, and the Scientific Revolution.

(In case anyone was wondering, I am not a Christian, and so these posts about religion do not reflect a bias on my part about which sect of Christianity is theologically correct).

Education

The place to begin when discussing the influence of Protestantism is education. Protestantism, in contrast to the Catholicism, insisted that every must read, understand, and interpret, the bible, and this necessitated mass education. In this respect, Protestantism caused Christianity to become more similar to Judaism than it had previously been.

Catholic nations, which had access to a printing press early than Protestants did but did not utilize it for the purpose of mass education, eventually educated their public as well, but this was in large part a response to competitive pressures placed on them by Protestants (Woodberry, 2012).

Consistent with this narrative, it has been shown that Protestantism was a significant predictor of literacy rates when comparing regions of 19th century Prussia. This effect persists after controlling for population sizes, live stock per person, the share of labor devoted to farming, businesses per capita, the number of schools per capita, and distance from Wittenberg

The same is true of 19th century Switzerland, though only in areas with conservative government.

More broadly, Protestantism was a significant predictor of the popularity of books in European nations between the years 1300 and 1800.

Today, Protestantism correlates with national IQ at .23, the IQ of the 95th percentile of a nation at .36, adult education levels at .48, and the prevalence of books at home at .62 (Rindermann, 2018, p. 162).

In most parts of the world, Protestants have higher levels of education than do Catholics. This is true of Protestant Europe, Catholic Europe, the Anglo world, and Africa, though it is not true of East Asia or Latin America.

Relatedly, Jeynes (2008) conducted a meta-analysis showing that students in protestant schools scored higher on standardized tests than did students at other sorts of private schools.

In an analysis of African nations, Gallego and Woodberry (2010) find that the historical prevalence of protestant missionaries has a positive effect on current levels of education. The same is not true of Catholic missionaries.

The same is found in analyses that include nations from all over the world.

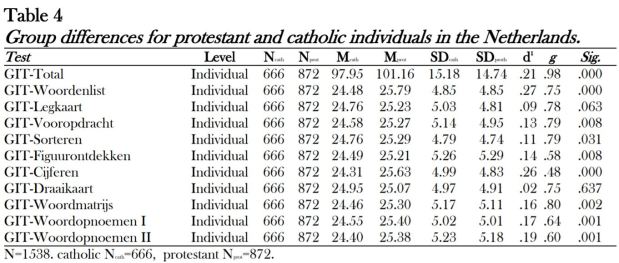

White Protestants also score higher than White Catholics on IQ tests. This has been shown to be true in America, Switzerland, and the Netherlands.

Thus, the empirical evidence is consistent the view that Protestantism spread mass education. This spread of mass education had a number of important direct effects. Here I want to mention only two.

First, it probably increased the population’s IQ. Today, meta-analyses indicated that education increases IQ, and I imagine that this effect would have been larger in the past when people were starting at a place of virtually no formal education (Ritchie et al., 2018). Moreover, longitudinal research has linked increases in IQ, and in education, to rises in wealth, suggesting that mass education likely contributed to the West’s massive rise in economic wealth (Rindermann and Becker, 2018; Bose et al., 2007).

Secondly, mass education was a key cause of what is known as the first demographic transition. For most of history, the world was caught in what is known as a Malthusian Trap. Populations responded to increased wealth by increasing their birth rates. This inhibited the degree to which wealth per person could grow. Around the time of the Industrial Revolution, the West experienced an increase in total wealth and falling fertility at the same time. This event, called the First Demographic Transition, allowed for massive increases in wealth per person and a major cause of this was mass education which incentivized people to spend their increased wealth on self development during their fertile periods. Importantly, statistical analyses have shown that schooling was far more important than than the direct effects of rising income in explaining this fall in fertility (e.g. Murtin, 2013).

Economic Growth

Turing from education to economic growth, Protestantism correlates at .30 with national wealth (Rindermann, 2018, p. 162).

However, current levels of Protestantism do not correlate with economic growth.

On the other hand, growth in Protestantism does predict modern economic growth even after holding initial national wealth constant.

So, the more protestant a nation is the richer it tends to be. And increases in Protestantism predict increases in wealth. But nations which have a high but constant level of Protestantism, while richer than average, are not growing in wealth at a faster than average pace. At least, that is what data on modern economies suggests.

Back in the 19th century, Protestantism was a correlate of national wealth, bank deposits, and the prevalence of stock exchanges. It was also a shockingly strong correlate of national savings rates even after holding wealth constant.

(Statistical note: the researchers involved in this paper, and the next, both, in my option, misuse significance testing. These papers report failing to find associations between Protestantism and economic outcomes despite findings correlations of practical significance. Their analyses have nearly no statistical power because their Ns are so small due to being aggregated national data points. The evidence they found is exactly what we would expect if Protestantism did have an economic impact, and so it is absurd to interpret this data as anything but support for that theory.

Now, significance testing tells you the probability that you find a sample such as the one you have found if that sample was pulled from an infinitely larger population in which there was no association between the variables being analyzed. In the case of national data on Europe, our “sample” is the population. There is no infinitely larger set of Europe a representative sample was pulled. Significance testing makes no sense in this instance, we are not trying to generalize onto a larger population, and significance has no relation to whether or not an association is truly causal, and so think it is appropiate to ignore these p values.)

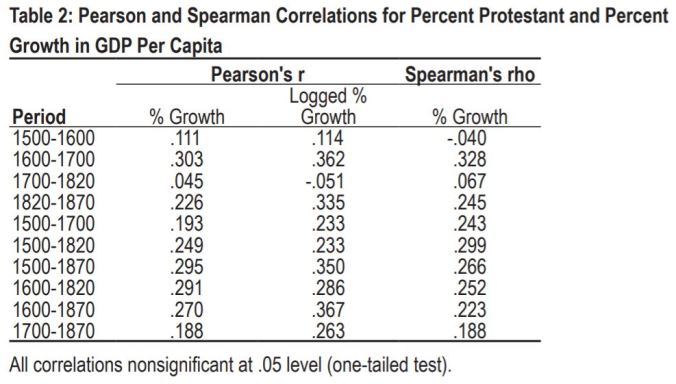

Protestantism was also a predictor of economic growth in Europe for most periods between 1500 and 1870.

However, this correlation was far from perfect.

Based on what we see in modern economies, there is some reason to think that this correlation might be stronger if growth in Protestantism was measured rather than initial levels of Protestantism, but so far as I know such an analysis has not be carried out.

Briefly, I want to consider two theories about why Protestantism seems to encourage economic growth.

The first concentrates on the effects of education. Support for this theory can be seen in work showing that regional Protestantism was associated with economic development in 19th century Prussia and modern Germany, but both these associations went away once education was held constant.

On the other hand, many have hypothesized that Protestantism leads to a stronger work ethic by theologically incentivizing economic successes and by harshly condemning hedonism. Supporting this view, Feldmann (2007) found that Protestantism was a significant positive predictor of national labor participation rates after controlling for government policy, economic growth, wealth per person, ethnic diversity, and other potential confounders.

It’s also been shown that protestants react more negatively to unemployment than to non-protestants.

These hypotheses are obviously not mutually exclusive. I find the education theory more compelling because there is strong evidence linking Protestantism to education and it is hard to see how this could not have a positive effect on economic growth, but it may be that the protestant work ethnic is an important contributing factor also.

Democracy

There is also a significant connection between Protestantism and democracy, especially in the form of republics.

In many ways, this is to be expected. Democracy was a revolt against pre-existing power structures throughout Europe and these were largely catholic. Protestantism naturally elevates the individual and is predisposed against centralized authority. Protestants were often persecuted for their religious views, and this plausibly caused them to favor forms of government which protect minority rights. Etc.

In the modern era, one of the first important advocates for republicanism was John Calvin. In the West, republicanism and democracy initially came out of protestant nations, especially Anglo ones. In the Protestant world, political revolutions tended to make societies more democratic (e.g. America). In the non-Protestant world, this is not how things tended to go, even when the revolutions were carried out by supposed democrats (e.g. France).

As time went on, many Catholic nations also became democratic but these democracies were often either short lived (e.g. 19th century France, 20th Century Latin America), or were forcibly imposed by Protestant nations (e.g. the world wars and the cold war). Even when not forced, Catholic nations moving into democracy often did so partly due to the Protestant influence on global power (e.g. Spain). And when Protestant nations have moved away from Democracy, this often done by non-protestant forces (e.g. Nazi Germany).

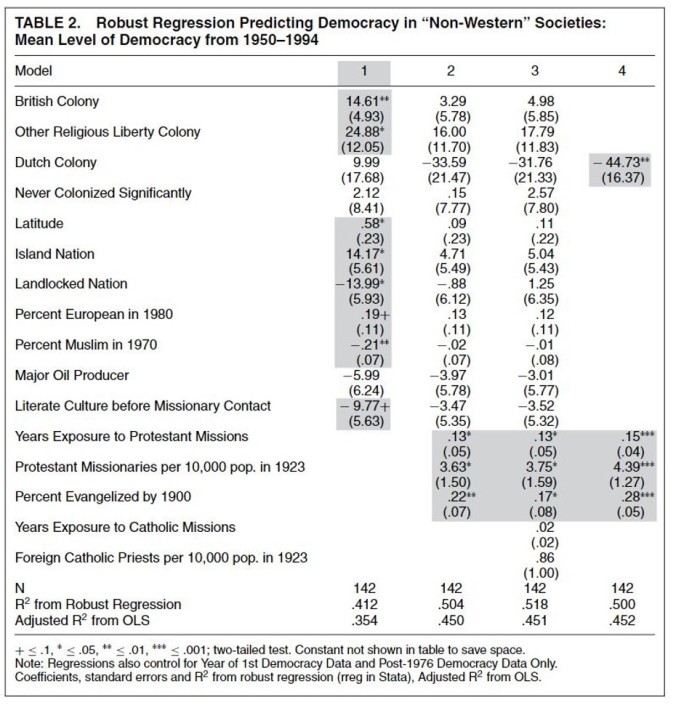

Moving away from Europe, since the 1970’s many non-western nations have made attempts at democracy. The vast majority of these have failed (Bizzarro and Mainwaring, 2019). Woodberry (2012) found that the historic prevalence of protestant missionaries, and protestant conversion rates, were both significant predictors of democracy in non-western nations. By contrast, the presence of catholic missionaries and priests had no predictive power. Controlling for Protestantism also eliminated the relationship between a non-western nation’s chance of being democratic, and its status as an ex British colony as well as the proportion of the country that is white. Controlling for Protestantism also flipped the influence of being an ex Dutch colony from positive to negative.

Other research, which includes Western nations, finds that Protestantism is a significant predictor of democracy even after holding constant the presence of early democracy, English influence, national wealth, and European ancestry.

(In the above paper, there are some regressions where the effect of Protestantism is similar to what is seen in this table but have a p value in excess of .05 due to a larger standard error. The same comments I made in the previous “statistical note” apply here. The only exception occurred when the sample was restricted to only British colonies where the predictive power of Protestantism was significant reduced. This is unsurprising though since this restriction of the sample also greatly reduces the variability in Protestantism.)

Other research has shown that states in governmental transitions are more likely to produce lasting democracies the more protestant they are.

Protestantism is also associated with the emergence of civil society, a feature commonly associated with democratic and individualistic civilization.

Thus, the relevant empirical data supports the view that Protestantism was an important cause of the spread of democracy.

The Scientific Revolution

Moving on from democracy, broadly speaking, there are three sorts of reasons for suspecting that Protestantism had something to do with the scientific revolution.

First, protestant theology is (relative to Catholicism) anti-authoritarian in nature and this seems naturally conducive towards science.

Second, significant scientific discoveries tend to come out of wealthy nations with high levels of intelligence and a non-authoritarian government.

As I’ve already argued, Protestantism helped to create all three of these conditions.

Third, protestants are over-represented among important scientific thinkers. This can be seen in two ways

First, Protestants account for more Nobel prize winners than their proportion of the population would predict, both globally and within the united states (Zuckerman, 1995; Shalev, 2002).

Second, since the spread of Protestantism important scientific innovations have been very heavily concentrated in Protestant areas.

Just prior to the spread of Protestantism, however, scientific innovation was not concentrated in North Western Europe.

Jews are the other religious group that tends to be over-represented in scientific achievement and, as I’ve already mentioned, Jews have an even longer lasting tradition of mass education than do protestants, and Jewish scientific ability was more freely expressed in the political context of the Enlightenment.

The empirical evidence thus seems to indicate the Protestantism was a causal factor in the scientific revolution, and we have good theoretical reasons for why this might be so.

Conclusion

In this post, I’ve argued that Protestantism was a contributing factor to the rise in wealth, education, democracy, and scientific innovation, that characterized the west over the last few hundred years. I’ve purposefully been light on historical narrative and relatively heavy on statistical evidence.

To reiterate, I am not claiming that Protestantism was the only cause of these things. It obviously was not. But I do think it was important. Protestantism has the virtue of being something that appeared and spread around the time that these things happened. This contrasts heavily with the, I think very weak, attempts to explain these phenomena by reference to Christian values more broadly (or, even more ridiculously, “Judeo-christian values”) that had been present for over millennia.

Protestantism also makes some contribution towards explaining where in Europe these things happened, which, again, vague appeals to Christianity cannot.

I think the gradual centuries long development of intelligence and individualism in North Western were also key causes of the things I’ve covered here. And I think both these variables increased the probability of the formation of liberal governments which in turn increased the ability of intelligence and non-conformity to translate into civilizational progress. I don’t think it is a coincidence that these are the places where Protestantism flourished. In my view, the interaction of these and other variables is what led to the explosion in development in North Western Europe.

Finally, I should note that I have ignored the connection between Protestantism and liberal ideology outside of advocacy for democracy. In another post, I noted that Catholicism is associated with leftism throughout the world today. In the past, the opposite was true, Catholicism was associated with traditionalism while Protestantism was associated first with classical liberalism and later with the Progressive Movement. Explaining this set of facts is complicated, and I’ve decided that it’s worth its own post separate from this one. So that is why I’ve left it unaddressed.

“First, protestant theology is (relative to Catholicism) anti-authoritarian in nature and this seems naturally conducive towards science.”

This is a crude generalization, and ignores the fact that that the modern scientific mindset is a product of the Catholic middle ages, fostered within the medieval church hierarchy.

https://www.catholiceducation.org/en/culture/history/medieval-science-oxymoron-think-again.html

https://www.catholiceducation.org/en/culture/history/medieval-science-oxymoron-think-again-part-2-of-3.html

https://www.catholiceducation.org/en/culture/history/medieval-science-oxymoron-think-again-part-3-of-3.html

And how can Protestantism, with its centralization of power within state churches, be considered anti-authoritarian?

LikeLike

Pingback: The Rise and Fall of Science | Ideas and Data

Pingback: The Rise and Fall of Science - GistTree

Reblogged this on Muunyayo .

LikeLike

Could the IQ gap be explained, I wonder, by selection for freethinking? To protest Catholicism in the beginning required a certain level of critical thought, not just for reformers but also for the citizenry who we’re told faced real consequences for choice. Surely the stressors in those times would have left genetic markers? Alas alack, tis but a thought, a scientist I am not. An armchair philosopher at best. Nevertheless! I enjoyed reading this, and will likely have to scan back a few times to get more out of the data. Thanks for posting!

LikeLike